Conventional agriculture has been instrumental in feeding a growing human population; much more so with the mechanization and synthetic fertilizer advances of the last century. But, as shown in the chart below, this approach had some deleterious effects on the environment and a search for alternatives began early in the 20th century.

The first movement away from conventional agriculture began in the 1920s in reaction to ecological and soil-related issues (Doring, et al.*):

... acidification of soils, loss of soil structure, soil fatigue, decrease of seed and food quality, and increases in plant and animal diseases were attributed to the chemical-technical intensification of agriculture. In addition, yield levels in Germany decreased drastically in the 1920s in comparison to the years before World War I, even though the use of mineral fertilizers increased.

This early movement toward organic farming focused on improved soil fertility and sustainability while reducing mineral-fertilizer use and producing high-quality crops.

Organic Agriculture

The United Nation's Food and Agriculture Organization defines organic farming as (Doring, et al.*):

... a holistic production management system which promotes and enhances agroecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles, and soil biological activity. It emphasizes the use of management practices in preference to the use of off-farm inputs ... This is accomplished by using, where possible, agronomic, biological, and mechanical methods, as opposed to using synthetic materials, to fulfill any specific function within the system.

The Rodale Institute defines organic agriculture as:

... a production system that regenerates the health of soils, ecosystems and people wherein, in opposition to the conventional approach, the farmer depends on natural processes, biodiversity and local-condition cycles to provide plant nutrition and fight pests and weeds.

But the organization does not see the farmer as only being involved with avoidance and substitution tactics; they are also engaged in proactive steps -- crop rotation, composted matter, green manure crops -- to improve soil health.

The table below captures the practices encompassed within organic agriculture.

Table 1. Organic Management Practices

Discipline

|

Practice

|

Action

|

Benefits

|

Soil Management

|

Cover crops

|

Planted between rows

|

|

Crop rotation

|

Different crops differentially on the same plot of land

|

|

|

Compost

|

Aerobic combination of traditional waste applied to soil

|

|

|

Organic No-Till

|

|

- Cover crops cut and left on the ground, forms thick mulch that suffocates weeds

|

|

Pest Management

|

Healthy soils

|

Prevention

|

|

Crop selection

|

Select pest-resistant varieties of crops

|

||

Pheremones

|

Disturb pest-mating cycles

|

||

Trapping

|

|||

Targeted sprays

|

|

Accoding to Doring, et al., land used for organic agriculture increased from 11 million ha in 1999 to 43.7 million ha in 2014 (the 2014 total represents approximately 1% of total available agricultural land). The market for agricultural products increased from US$15.2 billion to US$80 billion over the same timeframe.

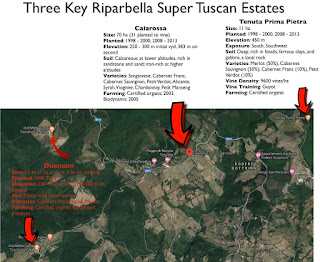

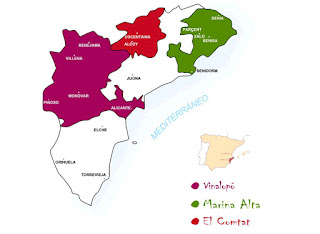

In viticulture, organic and biodynamic farming approaches were initially applied in the late-1960s with efforts focused on maintaining crop yields while improving soil fertility and reducing the use of mineral fertilizers. Today 316,000 ha of grapes are grown organically (4.55% of the global grapegrowing area), with Europe (266,000 ha) being responsible for the lion's share. Spain, Italy, and France have the largest organic grapegrowing areas. Worldwide, 11,200 ha of land are farmed, or are in transition to being farmed, under biodynamic principles.

Biodynamic Farming

Biodynamic farming, founded in 1924 by Rudolf Steiner, was one of the first movements towards organic agriculture. It is (Doring, et al.) "... a holistic agricultural system based on respect for the spiritual dimension of the living and inorganic environment."

Biodynamic agriculture is, for the most part, the organic agricultural system with extensions supporting application of specific biodynamic preparations -- said to stimulate soil nutrient cycling, promote crop photosynthetic activity, and transform compost -- along with adherence to the lunar calendar for certain agricultural activities. It should, ideally, be practiced on mixed farms -- including crops and livestock -- to meet Steiner's requirement of the farm as an organism.

Table 2. Main ingredients of the biodynamic preparations 500 to 507 (Source: Doring, et al.)

Preparation #

|

Designation

|

Main Ingredient

|

Use

|

500

|

Horn manure

|

Cow manure

|

Field spray

|

501

|

Horn silica

|

Finely ground quartz silica

|

Field spray

|

502

|

Yarrow

|

Yarrow blossoms

|

Compost

|

503

|

Chamomile

|

Chamomile blossoms

|

Compost

|

504

|

Stinging nettle

|

Stinging nettle shoots and leaves

|

Compost

|

505

|

Oak bark

|

Oak bark

|

Compost

|

506

|

Dandelion

|

Dandelion flowers

|

Compost

|

507

|

Valerian

|

Valerian flower extract

|

Compost

|

Healthy soils and crops are the foundation of biodynamic viticulture. According to adherents, if the microbiome of the soil is not healthy, the vine cannot get what it needs from the soil and can only survive with direct application of nitrogen. This "mainlining of nitrogen" prevents the vine from forming a normal healthy root system. Biodynamic viticulture seeks to "return the microbiome to a healthy balance so that the grapevine can return to its natural process of extracting what it needs from the soil." This makes for a healthier, stronger vine and more flavorful fruit and wine.

**********************************************************************************************************

This post serves as the baseline setting for future posts on comparisons of the approaches described herein and, further down the road, detailed research on regenerative agriculture.

*Johanna Döring, Cassandra Collins, Matthias Frisch, Randolf Kauer, Organic and Biodynamic Viticulture Affect Biodiversity and Properties of Vine and Wine: A Systematic Quantitative Review, Am J Enol Vitic. July 2019 70: 221-242.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme