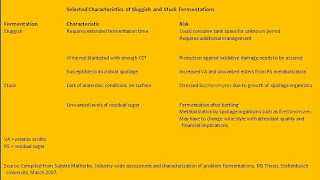

Slow or sluggish fermentation is characterized by low sugar utilization by the attendant yeasts while incomplete (stuck) fermentations occur when a higher-than-desired level of residual sugar remains at the conclusion of alcoholic fermentation (Klaus A. Sutterlin, Fructophilic yeasts to cure stuck fermentations in alcoholic beverages, PhD dissertation, Stellenbosch University, March 2010). Sluggish or stuck fermentations are the second most significant enological problem faced by winemakers (2003 American Vineyard Foundation survey and 1996 Association for the Development of Wine Biotechnology survey, both cited in Sutterlin 2010) and, with more than 60% of respondents admitting to having experienced one or both of these problems, the economic costs are perceived as being enormous.

Bisson and Butzke report that slow fermentation initiation (Type (i) in the foregoing) can occur in both natural and inoculated fermentations and, in the case of natural fermentations, "the sluggish start may simply be due to low numbers of yeasts in the must and not reflect any particular problem other than an initial low biomass." Based on their research, the authors aver that fermentation will go to completion, depending on juice conditions and the presence of other organisms, with as little as 100 viable Saccharomyces cells/mL present at initiation.

The risk of deficient (< 100 viable cells/mL) Saccharomyces populations leading to a problem fermentation is highest in the earliest portions of the crush. As crush is prolonged, Saccharomyces bacteria will colonize the winery equipment such that juice and must passing through said equipment will have their levels of Saccharomyces elevated.

In the cases where there are low initial levels of Saccharomyces, holding juice at low temperatures is risky as it (i) encourages the growth of Kloeckera apiculata and (ii) is injurious to the existing Saccharomyces yeasts. If the Saccharomyces yeasts are able to dominate, the fermentation will proceed to completion; if not, the fermentation will arrest. It should be noted that the lower the level of the initial Saccharomyces population, the greater the growth requirements of the juice. Bisson and Butzke estimate that it will take 13 generations to get from an initial level of 100 cells/mL to a typical innoculum level of 106 cells/mL.

According to Malherbe, stuck fermentations can be caused by glucose/fructose ratio imbalance, nutritional limitations of the must (nitrogen deficiency, oxygen deficiency, mineral deficiency, vitamin deficiency), inhibitory substances (ethanol, toxic acids, the effects of sulphites, killer toxins, fungicide/pesticide residues), and a number of physical factors (excessive must clarification, temperature extremes, excessive use of Sulphur Dioxide). When compared to this range of potential stuck-fermentation causative factors, the risk of low initial yeast population in natural fermentations does not seem that stark. Bisson and Butzke has shown that fermentation can conclude successfully even beginning with yeast levls as low as 100 cells/mL and if the fermentation continues in a sluggish manner, or gets stuck, it is a biomass rather than a starter problem. Further, the risk of sluggish initiation is not restricted to natural yeast fermentations. According to Bisson and Butzke, poor starter culture can lead to sluggish initiation in the case of inoculated fermentations.

To conclude then, sluggish/stuck fermentations is an issue that a winemaker always has to be cognizant off and has to constantly monitor against. There are many opportunities for this curse to be visited upon the winemaker and one of those cases is at the initiation of the fermentation where it will register as a sluggish start. Such a manifestation could be apparent whether the fermentation is natural or inoculated. All things being equal in the biomass, the natural yeast fermentation should right itself and proceed to completion. There does not seem to be an outsized and determinative risk of stuck fermentations if one practices natural yeast fermentation. There is an obvious lag phase however, as the yeast levels build up from cellar-entry levels to standard starter inoculate levels.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

No comments:

Post a Comment