The entry of

"non-local" producers has long been a hallmark of winemaking on Mt Etna but a blue whale landed in 2017 with the announcement of a 50/50 joint venture between Angelo Gaja and Alberto Graci for the production of wines on the mountain. According to doctorwine.it, "The arrival of Angelo Gaja ... was one of the most important events in the recent history of Etna wine. The attention from a producer of such great and recognized prestige has confirmed the undisputed value of the volcano's terroir, strengthening its image and consolidating its position among the most interesting areas in the world for wine production."

Initially unnamed (subsequently called Idda -- "she" in local dialect -- a reference to the ever-present volcano), the venture --valued at €4 million by Club Oenethique -- was launched with the acquisition of the Masseria Setteporte vineyards (with the exception of 10 ha surrounding the Portale homestead). I herein reflect on the joint venture and taste two examples of its wines.

The Partners

Angelo Gaja

Angelo Gaja is, according to

BBR, "... Italy's most renowned and dynamic wine personality and his impact on wine production in the last 30 years cannot be overestimated."

The 5th generation of the family to manage the estate founded in 1859 by Giovanni Gaja, Angelo began working at the winery in 1961 after completing Enology studies at Alba and Montpellier. He took the reins of the business in 1970 and initiated a number of groundbreaking and, in many cases, controversial practices. He installed temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks, aged wines in barriques, was the first to release single-vineyard Barbarescos, released wines that did not conform to regulations, and re-introduced French varieties to Piedmont. Controversies notwithstanding, the quality of his wines were high and customer acceptance unparalleled.

Today Gaja farms 101 ha in Barbaresco and Barolo in addition to efforts in Alta Langa (30 ha), Montalcino (Pieve Santa Restituta), and Bolgheri (Ca'Marcanda).

Alberto Graci

Alberto Graci is of Sicilian farming stock but left home to pursue studies in Rome and an investment banking career in Milan. He returned to Sicily upon his grandfather's death and sold the farm in order to buy vineyard property on Mt Etna. Alberto arrived on the mountain in 2004 and purchased property on its northern slope. In New Wines of Mt Etna, Benjamin North Spencer relates the Graci entry to the region as follws: "Many people come to Etna for a slice of adventure. But it was curiosity that first drew Alberto Aiello Graci to the mountain." Once he got there, though, " '... it was the honorable history ...' " that made him want to stay.

Graci's current holdings include Contrada Arcuria (20 ha), 80-year-old vines (1.5 ha) in Contrada Feudo di Mezzo, young vines in Contrada Muganazzi (5.5 ha), young vines in Contrada Santo Spirito (0.9 ha), and 100-year-old vines at 1000 m in Contrada Barbabacchi (2 ha). The estate pursues full maturity of the major native varieties in a certified-organic environment with vinification and aging of harvested grapes occurring in concrete tanks and large oak barrels.

Idda Vineyard Holdings

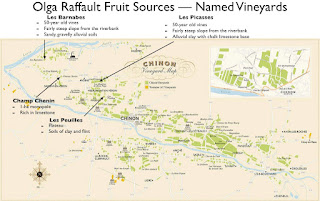

The figures below show the municipality-level locations of the Idda vineyards and the associated growing environments.

|

| Map courtesy of Cittavino |

The Biancavilla holdings were

described previously while Monica Larner describes Belpasso as "a little island of soil sandwiched between more recent lava flows" and the Idda vineyard therein as being resident on "rocky volcanic soils."

The Tartaraci vineyard is located on the northwestern flank of the mountain at 1000 m elevation. The property was once owned by Lord Admiral Horatio Nelson, bequeathed to him by the Kingdom of Naples for seeing off the French in 1799. The vineyard is planted to 90-year-old bushvines of Nerello Mascalese, Nerello Cappucchio, Garnacca, Grecanico, and Carricante. The vineyard, typically one of the latest on Etna to be harvested, lies outside of the DOC zone. Frank Cornelissen and Buscemi source grapes from Contrada Tartaraci.

According to Monica Larner (Wine Advocate), Idda's goal is the production of 90% whites and 10% reds as its final wine composition and has planted 12 ha of Carricante over the last 3 years in pursuit of that goal. In discussing the growing strategy in the south, Gaia Gaja indicates that they are planting on "hotter, more exposed terroir ... to try harvesting the white Carricante grape earlier and thus retain more of its celebrated acidity while giving it a bit more body." Further, they would like to move higher up on the slopes in the future as insurance against climate change.

The Wines

Idda currently produces a white (100% Carricante) and an Etna Rosso. I tasted the 2020 version of the former and the 2018 version of the latter.

The white wine is classified Sicilia DOC. The wine is whole-bunch-pressed before cold decantation and fermentation in stainless steel tanks. The wine is aged for 1 year in 15 l oak casks and stainless steel tanks.

I have tasted Carricante-based wines from all faces of Mt Etna and, more specifically, I have tasted Benanti, Tenuta di Fessina, and Feudo Cavaliere whites from the southwest, and I find no typicality in this wine

vis a vis these others. In my

tasting of Carricante-based wines, I stated thusly: "Carricante-based wines from the east to south flanks of Etna are characterized by salinity, minerality, and acidity and, at its optimum, these characteristics meld extremely well." The Idda white showed a perfumed nose with lime and lime skin and a honey-dew melon undertone. Light-bodied and unfocused with low-grade acidity, missing salinity, and a lack of complexity.

Salvo Foti says that it takes between 10 to 15 years for Carricante juice to show concentration and I wonder if this is somehow involved here. Or this could have been a bad bottle of some sort. I will continue to explore to see if I get similar characteristics in future bottles.

The Etna Rosso was more readily identifiable as such. Ripe plum and vanilla bean on the nose. Light-bodied and smooth on the palate with broad-based fruit and low acidity.

Some Observations/Thoughts/Questions on the Joint Venture

The joint venture serves as a vehicle for Gaja's entry into the Etna marketplace. This means that Gaja sees the market as underperforming and sees himself being able to capitalize on the upside potential. That upside potential may be realized organically or by Gaja's entry or by future things that he brings to the table.

It is a feather in Mt Etna's cap for Gaja to be making wine on the mountain and is definitely a feather in Graci's cap for him to be a part of the team. Why did Gaja pick Graci? Someone of Gaja's stature could have had his pick of partners from among the producers. There is some discourse that Gaja had met Graci previously and liked his spirit. There is also the sense that Gaja wanted a local expert to serve as a guide. But Graci, even though Sicilian, is not from Mt Etna. Further, his entry to the market came after "foreigners" like Franchetti and Cornelissen had already entered the market. The Salvo Foti-Rhyss Vineyard joint venture was a more classic insider-outsider play. In any case, given the passage of time, and the effort that they have expended, those early entrants have probably earned "insider" status by now.

In terms of experience, Graci is very involved with properties on the north face of the mountain so I found it intriguing that all of the properties involved in the JV are on the southwest and northwest faces. The best locale for white grapes on Mt Etna is the east face and if one is looking to make a great white wine, that is the terroir that I would have expected to see engaged. It is true that Benanti, Feudi Cavaliere, and Tenuta di Fessina all have white wines from the southwest but their primary white wines are from the east.

There appears to be some opportunity to beneficially leverage the Gaja name. Vineyard prices in the southwest and west are lower than in the east so the cost to get the project fully up and running would be lower in the former than in the latter. Meanwhile, the Gaja market power can be leveraged to price the wines aggressively (for example, a 2019 Masseria Settoporte is about $25 while a 2020 Idda is about $50), shortening to time to breakeven.

Salvino Benanti thinks that winemaking on Mt Etna will become an oligopoly in the near-term with winemakers being forced to make investments to stay competitive. There is no doubt that Idda has the resources to play -- and win -- in that game.

©Wine --

Mise en abyme