The Spanish were directly responsible for the drubbing of French wines at the hands of the American upstarts at the Judgment of Paris tasting. More specifically, Spanish priests were the culprits. It's a long story -- told in two parts -- so strap in.

European wine grapes (vitis vinifera) were first brought to the New World by Christopher Columbus on his second voyage (1493 - 1496), the first installment in the Columbian exchange. Columbus brought settlers and seeds and cuttings for wheat, chickpea, onions, grapes, olives, sugar cane, and fruits on that journey with the express intent of settling the island of Hispaniola. The Caribbean provided less-than-ideal conditions for grapegrowing and this initial attempt at making wine in the New World was a failure (as was also the case for grain and olives). At this point the French wines were still ahead; but so was Mexico.

Mexico

Presented with a second opportunity to protect the self-respect of the wines of its fellow continental traveler France, Spain demurred and took a second bite at the apple of wine production in the New World.

Pre-Columbian Mexico was home to grapevines. The inhabitants of the time used the grapes to make a drink which included other fruits and honey. The Aztecs called the fruit of the vine acacholli, while the Purépechas (seruráni), the Otomis (obxi), and the Tarahumaras (uri) all had their own nomenclature. These grapes, primarily due to their high acidity, were deemed by the Spanish conquistadores to be unsuitable for the production of wine.

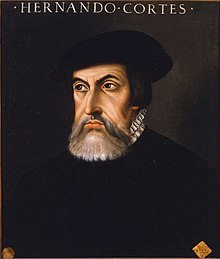

The Spanish had vitis vinifera vines in their possession, however, and began planning for their deployment. On March 20, 1524, Hernan Cortes, conqueror of the Aztecs and Governor of New Spain, ordered each lieutenant to plant the equivalent of 1000 feet of vines for every 100 slaves they possessed.

|

| Hernan Cortes |

This order fueled a significant expansion of the vineyards around Mexico City in the areas of Tacubaya, Puebla, and Hidalgo. Vines were cultivated immediately by the priests who needed wine for the celebration of Mass. According to one source, "They were the ones who transformed inhospitable deserts into areas of cultivation and wine-growing." The Jesuits and Franciscans consolidated the grape varieties planted by other friars and named it the "mission grape."

The expansion of wine production continued with vines being planted northwards from Mexico City to Querétaro, Guanajuàlo, and San Luis Potosi. Vines were very successful in Parras Valley and, subsequently, Baja California, Sonora and the Puebla vineyards Tehuacan and Huejotzingo.

Parras Valley is the largest and oldest grape-growing region in Mexico. Wild vines were found in the valley by priests and settlers exploring the area in 1549 and they founded a mission there, naming it Santa Maria de Las Parras (Parras translating to vines). The mission made wines from the wild grapes and were soon shipping wines and brandies from this region to other parts of New Spain. Mission grapes also did well here and cuttings eventually made their way north to the formative Napa Valley. The Marqués de Aguayo winery was founded in Parras Valley in 1593. The winery officially ceased business in 1989.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

As the Mexican wine industry flourished, less wine was imported from Spain, a distressing state of affairs for Spanish producers. They petitioned the King (Philip III) and he issued an edict in 1595 banning the production of wine and the planting of new grape vines anywhere in New Spain. In spite of the ban, he issued commercial rights to Don Lorenzo Garcia allowing the production of wine and brandy. Don Lorenzo founded the Hacienda de San Lorenzo winery in Valle de Parras in 1597 to exploit his license. The winery is still in operation today under the name Casa Madero.

Winemaking continued to flourish in New Spain prompting Charles II to issue an edict in 1699 banning the production of wine in New Spain except for sacramental purposes. This religious exception allowed a Jesuit priest to plant the first vines in Baja California at the Loretto Mission. In 1791, Jesuit Priests attempted to revitalize large scale production at the Santo Tomas Mission in Baja California. In 1843, Dominican Priests planted grapes at a mission in today's Valle de Guadalupe. The Mexican Reform War of the 1850s called for many of these lands to be returned to the state. The Santa Tomas Mission was sold to a group of investors and became Mexico's first commercial winery -- Bodegas Santo Tomas.

Colombia

Jesuit missionaries brought vines into Colombia from Mexico in 1530 and succeeded in crafting some wines but were forced to discontinue production after the 1595 ban by Philip III.

Peru

The first vines were planted in the heights of Chile in the 1540s but farming them was laborious so they were moved downhill towards the coast in the vicinity of Ica. The original vines were planted to suport the Catholic mass but the locals began enjoying the wine out of church as well. The wine became so well known that it was exported to Bolivia to fuel the entertainment needs of Potosi, the then "Paris of South America."

The Spanish ban on local wines caused some producers to bargain with the Crown to produce a local aguardente -- the birth of Pisco -- while others switched crops, and the remainder continued quietly producing wine.

Chile

The first grapevines were brought to Chile in 1548 by Francesco de Carabantes, a Spanish Friar. The first Chilean grower was Francisco de Aguirre, who delivered his first harvest in 1551. Other sources credit Rodrigo de Araya who was cultivating grapes in the Chilean Central Valley at the same time. Pretty soon vitis vinifera was cultivated along the length and breadth of Central Chile and Spanish-sourced varieties dominated the Chilean wine scene until disrupted by French varieties beginning in 1851.

Bolivia

Grapevines were first planted in Bolivia by Spanish missionaries in the 1560s but the tropical climate proved inhospitable to vitis vinifera.

Argentina

The first cuttings planted in Argentina were brought in from the Chilean Central Valley in 1556 by one Father Cedrón. The first small plantings occurred in San Juan and Mendoza but by the end of the 16th century vineyards could be found in every settled region.

Growers gravitated to the Cuyo region over the first 200 years due to its high altitude, favorable climate, and plentitude of water. A total of 120 vineyards were located in Mendoza by 1739.

Grape Varieties

During the first 100 years of viticulture in the above discussed regions, missionaries brought over a number of grape varieties either in the form of seeds or sticks. The white varieties included Muscat of Alexandria, Mollar, and Palomino while the red was Listán Prieto. The Listán Prieto was the most significant planting and is sometimes referred to as the mother grape of the Americas.

Listán Prieto is native to the Castille region in Spain and was brought to the Canary Islands where it flourished. There are very limited plantings of this variety in Castille today with some supposition that it was wiped out by Phylloxera.

When brought to the Americas, the variety was generically called Criolle but had different names depending on location: Mission in Mexico, Negra Criolla in Peru, Pais in Chile, Missionera in Bolivia, and Criolla Chico in Argentina. This variety represented over 90% of the plantings in Argentina and Chile in 1833.

With the passage of time, crossings of these founding varieties occurred with Torrontés in Argentina being the most significant. There are three different Torrontés varieties: Torrontés Riojano, Torrontés Sanjuanino, and Torrontés Mendocino. Some 150 native criolla varieties have been identified to date.

No comments:

Post a Comment