The wine world has been wracked by a number of leading-light deaths in the past two years or so but none has struck as close to home for me as the passing of the Tuscan and Mt. Etna giant Andrea Franchetti. I have eaten and drunk wines at both of his estates and been the beneficiary of a wealth of information and insights that he has directed my way. But not only did I benefit from knowing Andrea, I also benefited from the organizations and institutions that he established. The staff at both of his estates are some of the nicest, most helpful people that you would want to meet and Contrada dell'Etna, his formualtion, continues to be one of the most efficient methods for surveying the breadth of Mt Etna's offerings. I seek to honor Andrea by providing an overarching view of the structures that he built and the products that he offered.

|

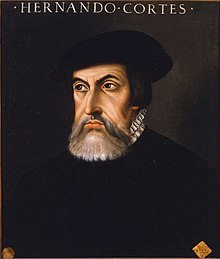

Andrea Franchetti

(Source: Letizia Patanè) |

Andrea Franchetti came from a famous and wealthy Roman family linked to the Frankfurt Rothschilds but struck out on his own and built a superlative brand in the wine industry.

Andrea had been a wine broker and imported French and Italian wines to the US between 1982 and 1986. He wanted to come back to Italy but, before doing so, went to Bordeaux and spent some time learning winemaking from his friends Jean Luc Thunevin (Chateau Valandraud) and Peter Sisseck (Dominio de Pingus). He then returned to Italy and single-handedly build two wine estates --

Tenuta di Trinoro (Tuscany) and

Passopisciaro (Mt. Etna) -- from the ground up, the former focused on wines made from Bordeaux varieties and the latter, primarily wines from traditional Mt Etna varieties.

Tenuta di Trinoro

In 2002 Jancis Robinson described Andrea Franchetti's Tenuta di Trinoro as an "idiosyncratic wine estate ... which has achieved quite remarkable renown considering it was first planted in 1992." Antonio Galloni, writing on vinous.com, described the estate as giving "new meaning to the expression 'in the middle of nowhere.'"

Armed with philosophies, practices, and cuttings that he had secured from his Bordeaux friends, Andrea went to the Tuscan hinterlands, to land that to him was reminiscent of the left- and right-bank Bordeaux soils, and bought the 200-ha property that is Tenuta di Trinoro.

The Val d'Orcia area in which Tenuta di Trinoro is located had been almost abandoned between 1960 and 1980 with the primary activity being sharecropping. Sheep-breeding came with the Sardinians when they emigrated here between 1960 and 1970. The houses in the area were primarily second homes for the wealthy.

Given its location, Tenuta di Trinoro gets sufficient sunlight to bring its grapes to maturity during the course of a growing season. Up until 2004, the area experienced Mediterranean growing seasons (mild, wet winters and warm, dry summers) but the growing seasons are now more tropical; that is, more rain and cooler summers (Andrea said that these new seasonal effects allow them to make better wines than they could with the scorching Augusts of the past. The prior August heat left the vines paralyzed which lengthened the ripening process and brought up the sugar. These are much better years, he says, with 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015, and 2016 all great vintages. He also pointed out that the concentration is better under these new growing conditions.).

Plants are kept low -- Bonsai vineyard concept -- with each allocated 1 sq meter of canopy. Sheep manure is the only type of fertilization used on the property and spray material consists of copper and sulfur. A mix of clay, propolis, and grapefruit seed extract is sprayed in the pre-harvest period to ward off botrytis and other molds that may occur on the grapes as they approach full ripeness. There is no irrigation except for newly planted vines.

Vini Franchetti characterizes its vineyard work at Tenuta di Trinoro as follows:

We generally every year go into the vineyard and treat every vine 20 to 25 times during the growing season: to thin, hold up, cut away, spray glues or powders, hoe and dig, top and pick. We then do innumerable pickings for two months at harvest. In the winter four more long visits are spent on each vine to prune, tie, and to mend the poles and wires,

As he does at

Passopisciaro, Andrea walks the vineyards at Trinoro incessantly. He makes the decision to pick based on taste. Each plot is harvested, vinified, and aged separately according to the process shown in the chart below.

As regards the wines, the

Le Cupole is the estate's second label. The 2015 edition is a blend of 58% Cabernet Franc, 32% Merlot, 6% Cabernet Sauvignon, and 4% Petit Verdot. The yield was 50 hl/ha. We tasted a cement vat sample. Concentrated with soft tannins.

The

2014 Magnacosta is a 100% Cabernet Franc which, like the other crus, had been aged in new oak for 8 moths and then transferred to cement vats for an additional 11 months of aging. The year had been cool but the grapes were ripe and showed as sweet and concentrated in the wine. Herbal and peppery with well-integrated tannins.

The

2014 Tenaglia showed black and blue fruits, licorice, and tea. Fruit carries through to the palate. A little more power than was the case for the Magnacosta. Salinity. Lengthy finish.

The

2014 Carmagi was not giving on the nose. Blue fruit, duskiness, and salinity on the palate.

The fruit was so good in 2009 that Andrea resurrected the Palazzi as a wine in that vintage. We tasted both the

2009 Palazzi (100% Merlot) and the

2009 Tenuta di Trinoro (42% Cabernet Franc, 42% Merlot, 12% Cabernet Sauvignon, and 4% Petit Verdot) but both were too cold to reveal themselves fully. The Palazzi showed mushrooms, a savoriness, and a hint of green. Mineral finish. The Tenuta di Trinoro did not reveal much on the nose and opened up just enough to give a hint of layered complexity.

A subsequent re-tasting of the

Tenuta di Trinoro showed intense spice and dark fruits on the nose along with leather, cassis, and licorice. On the palate, dark fruit accompanying a rich, thick creaminess and beautifully integrated tannins. A long, rich, creamy finish. The

Palazzi showed ripe dark fruit, licorice, spice and chocolate. Balanced. High note resulting of pleasing acid levels. A creamy finish.

Bianca Trinoro

In the same year that he launched his inaugural Mt Etna vintage -- 2001 -- Andrea planted some Semillon vines at his Tuscan property. According to Wine Searcher, the property had a sandy patch at its highest reaches (0.6 ha at 620 m). This plot reminded Andrea of the Medoc, prompting thoughts that it might be suitable for a white variety. Given the Bordeaux profile of the estate, he opted for Semillon as that white variety.

The vines are planted at 10,000 vines/ha with yields of 25 hl/ha. According to Andrea, he made 1000 bottles of wine from the harvested fruit each year and drank them after each vintage had matured for 10 years. After drinking the wines over the years, he got to a point where he felt that the vines had matured enough to support a high-quality commercial offering. This led to the release of the 2017 and 2018 vintages on the market.

The grapes are harvested manually and then transported to the cellar where they are whole-cluster-pressed and then fermented. The 2018 vintage was fermented in stainless steel tanks for a total of 10 days (the 2017 vintage appears to have been fermented in barrels) and then aged (on lees) in cement tanks for 7 months (the 2017 vintage was aged in glass demijohns as they awaited delivery of the cement tanks).

Andrea viewed the wine as being approachable after 5 years but it will not reach its peak until 10 years have elapsed.

Even though Andrea thought the wine should be hidden for its first 5 years, it more than showed its mettle when I tasted the 2018 version. In the early stages of the tasting it showed rosemary, apple, dried hay, and intense herb/florality, spice, and menthol. As it evolved, a sweet white flower and creamy vanilla with an attendant richness and complexity. With additional time, green herbs and talcum powder.

On the palate, lemon-lime, salinity, a marine character, a stemminess from the whole-cluster-pressing, and a drying, limey finish. With time, a blade-like precision, lime, and spiciness. The sweetness which is pervasive on the nose does not carry through to the palate. Gains weight with time.

This wine is replete with promise.

Passopisciaro

According to Nesto and di Savino (

The World of Sicilian Wine):

In 2000 Etna's wine industry awakened suddenly. Foreign attention and capital arrived. The newcomers Frank Cornelisen from Belgium, Marc de Grazia from Florence, and Andrea Franchetti from Rome bought vineyards on Etna and became evangelists of its potential (Ed. note: Andrea stipulates that Marc de Grazia came to Etna a little after Frank and him.).

Andrea came to Etna looking for high-altitude vineyards where the grapes would mature in the cool of autumn and settled on Passopisciaro on Etna's north face.

Guardiola, a 8-ha property just on the edge of the DOC, was bought in 2002 (Some of the vines are DOC and others are not). Two hectares were planted to Petit Verdot in 2001/2002 at between 800 and 1000 m altitude and another 2 ha to Cesanese d' Affile. These vines were planted at 12,000 vines/ha with 5 bunches/vine. The vines were subjected to green harvests in order to further concentrate their energy and are the sources of the Franchetti wine first introduced in 2005. The current configuration of Guardiola is 3 ha split between Chardonnay, Petit Verdot, and Cesanese d'Affile and the remainder dedicated to Nerello Mascalese.

Franchetti's first wine was a Nerello (Passapisciaro 2001) but, as he stated in a personal communication, "I tried to make a Nerello that I liked right away, but wasn't able, until 2005 when I finally started getting it. Since then our Nerello has been, I think, getting better because of new touches in the winemaking."

Robert Camuto (Palmento: A Sicilian Wine Odyssey) provides telling insights into the Franchetti mindset and practices in those early years. In his visit to the Franchetti estate in the summer of 2009, he saw no Nerello Mascalese grapes planted there. In fact, "... Franchetti saw no need to plant local varieties when he could buy or lease Nerello from vineyards that were already established."

His perception of this early-times Franchetti is electric:

Most winemakers were coming to Etna to make their interpretations of Nerello, but Franchetti was here, it seemed, to interpret Franchetti. The others were like landscape painters who had come to paint the volcano; Franchetti was an abstractionist who had come to paint on the volcano. ... For other winemakers, Nerello Mascalese, with its delicate Pinot Noir color and structure, was part of the attraction. Franchetti, on the other hand, was here on Etna in spite of Etna.

Camuto reports that Franchetti told him, "I hated the stuff -- I thought it was coarse. I didn't want to use Nerello to make wine. I looked at it as an ingredient I had to use."

According to Camuto, the early Franchetti Nerello vintages "rolled out the Bordeaux new wave formulas that had worked so well for him at Tenuta di Trinoro" but the long maceration, and aging in

barriques, produced a wine that was "as rude as it was rustic."

In an email communication with me, Andrea referred to the wines made before 2004 as the "pre-Socratic vintages."

In 2004, I tried to extract for a long period at low temperature before fermenting the berries; to no avail. I mixed some 2001 Trinoro Merlot in the 2002 Nerello Mascalese. I let the 2003 Nerello Mascalese start out with local wild yeast out of spite. No "philosophy" had been built.

Andrea sent me three of these early vintages to try. They bear no resemblance to the Franchetti Nerello Mascalese wines of today.

The

2001 showed a much deeper color than one would expect from an aged Nerello Mascalese. Hint of Nerello on the nose, but indistinct. Mushroom and earthiness dominates. Concentrated and unfocused on the palate. Bitter on the palate with a very bitter aftertaste. Metallic. Unpleasant finish.

The

2002 showed balsamic, spice, dark fruits, and lacquer on the nose along with hints of tobacco and cedar. Fruitier than the 2001. High acid level. Lack of focus on the palate. Big, dark fruit. red pepper spice. Bitterness and acidity competing on the palate. Severe dryness on palate leading to a furry feel in the mouth.

The

2003 exhibited stewed fruit, spice, and rust. Sweet fruit on the palate. Bitterness, salinity and kerosene.

But Franchetti eventually came to the realization that the problem was with his winemaking technique, rather than with the cultivar and, in 2004, he changed his approach (Camuto):

- He ceased macerating on the skin

- He lowered the fermentation temperature

- He moved from barrique to botti for aging

Franchetti, as cited by Camuto: "You see, I learned that the best part of the Nerello grape is not in the skins, like with the Bordeaux grapes. Its all in the juice."

In his communication with me, Andrea said that he gained his initial feel for Nerello in 2004 when the wine came in "nice and tannic." The first applied thinking happened the following year (lightness, clarity, fining with egg whites). "What Nerello wine should be, or is in the heavens, struck me from 2005 on: I first modified the cellar activities, then the harvesting decision; then my vineyard management practices."

And the rest, as they say, is history.

He began planting Petit Verdot which he blended with Cesanese d' Affile to make a wine he called Franchetti.

Once Franchetti was introduced, Andrea pivoted and sought to make a great white wine from Chardonnay (first bottling in 2007) and Nerello Mascalese wines that reflected their terroir (first bottling of Contrada wines in 2008) . The distribution of vines by

contrada, and the individual contrada characteristics, are shown in the figure below.

|

| Source:vinifranchetti.com |

In order to ensure that any differences in the wines are contrada-specific, the wines are given the same vinification treatment: fermentation in steel vats; malolactic and 18 months aging in large neutral oak barrels; fining with bentonite; and no filtering. The Franchetti is aged in barrique.

We began our tasting with the

2015 Passorosso (Passopisciaro until a few years ago). The grapes for this wine are sourced from 70 - 100-year-old, bush-trained vines grown at altitudes between 550 and 1000 m in the contrade of Malpasso, Guardiola (40% of grapes), Santo Spirito, Favazza, and Arcuria. High-toned red fruit with smoke, leather, and mineral notes. On the palate, bright red fruit, acidity, with drying tannins on the finish.

The

2015 Contrada Rampante was made from 100-year-old-vines which are planted at 8000/vines/ha and yielded 17.6 hl/ha. Herbs. smoke, iron, sweet tar, tobacco, and spices. Good fruit levels but not as focused as I would have liked.

The

Contrada Chiappemaccine 2015 was the least complex of the wines I had tasted up to this point. Not very giving on the nose and non-complex on the palate. The

2014 edition of this wine showed fresh red fruit, sweet herbs and spice. Tobacco on the palate.

The

2014 Contrada G was elegant. Smoke, tobacco, leather, and sweet tobacco. Savoriness. Complex, big fruit but balanced by acidity. Silky tannins. Long finish.

The

Franchetti 2014 is a blend of 70% Petit Verdot and 30% Cesanese d' Affile. Yields of 17 hl/ha. Fermented with selected yeasts in stainless steel tanks for 10 - 15 days. Malolactic and 8 months aging in barriques, followed by 10 months in cement and 2 months in bottle. Bentonite fining. Rich, inky, with herbs and smoky barrel notes. Powerful. Not a classic Etna wine but I loved.

Andrea Franchetti's Mt. Etna Chardonnay Journey

When he arrived on Mt Etna in 2002, Andrea decided to restore some ancient terraces lying between the Guardiola and Passochianche Contradas and to plant the plots to Chardonnay rather than Carricante, the latter being best suited to the clime and soils of the eastern slope. The vines were planted at elevations ranging between 850 and 1000 meters in "very loose, deep, powder-like," mineral-rich lava.

In 2009, Andrea planted an additional parcel of Chardonnay in Contrada Montedolce.

Andrea's intent was to craft a long-lived Chardonnay reminiscent of the wines of Burgundy and, towards that end, planted at 12,300 vines/ha in order to force inter-vine competition and the production of small, concentrated berries. Andrea felt that the combination of stressed fruit, altitude, abundant sunlight, and significant day-night temperature excursions would produce wines with excellent body plus the acidity and minerality for which the zone is famed.

The first Chardonnay was introduced in 2007. It was called Guardiola initially but, since 2014, is called Passobianco. This 100% Chardonnay utilizes fruit from all Passopisciaro Chardonnay plots.

On every occasion that I have been to Passopisciaro, I have seen Andrea walking through the vineyard, plucking something here, tasting something there. So he knew the vineyards like the back of his hand; and he noticed that as the vines became older, individual plots were developing distinct characteristics. In 2018 Andrea decided to utilize his knowledge of the vineyard characteristics to bottle a Contrada Chardonnay using grapes drawn solely from one of the highest parcels (870 - 950 m) in Contrada Passochianche. The resulting wine is called Contrada Passochianche.

The fruit sources for the Passopisciaro Chardonnays are summarized in the chart below.

The first-ever edition of Contrada Passochianche was 2018.

According to Passopisciaro, 2018 "was one of the rainiest and most tropical vintages that we've seen on Etna in the last eight years, especially at the end of the summer." The number of leaf-pull passes through the vineyard had to be increased in order to provide air passage through the vines and mitigate the effect of the humidity. Additional mitigation efforts included the use of products such as clay, propolis, grapefruit seed extract, copper, and sulfur.

The harvested grapes were destemmed and cold-soaked for 12 hours. They were then fermented in large neutral oak barrels of no more than 20 Hl, followed by malolactic fermentation in barrel. The wines were aged on lees for 10 months in large neutral oak barrels and for an additional 12 months in bottle.

This wine was alive, taking on different characteristics as it spent more time exposed to the light of day. It was popped and poured.

One of the first things that I noticed was the extremely high surface tension of the wine. I felt like even I could walk on that water.

Restrained on the nose initially with hints of herbs, sweet white fruit, apple, and peach. Weighty on the palate at first blush. Bright, intense, racy acidity which was instantly ennervating of the salivary glands. Citrus. Palate-coating chalky limestone and a peppery cupric finish.

The altitude is apparent, imparting a chiseled character. With the passage of time, a complex mix of minerality, acidity, bitterness, and slate on the palate and the finish.

The nose opens up to reveal tropical notes to include pineapple. As the initial bright acidity recedes, citrus (lime) and minerality rule the day. The wine continues to excite the salivary glands but in a less whole-palate manner.

The wine becomes less weighty over time with lees and honeydew melon making their presence felt. More linear on the palate with consistent minerality and lime and a saline intrusion. Bitter finish with a lean, mineral, wet-rock aftertaste.

This is a complex wine which has all the characteristics and stuffing to hang around for a while.

Contrada dell'Etna

In 2008 Franchetti created and sponsored a wine fair called Le Contrade dell 'Etna where the region's producers showcase their wines -- within the contrada context -- to the wine press and enthusiasts. Brandon Tokash recounts receiving a call from Andrea one Christmas wherein Andrea discussed his idea for a gathering of north-slope producers to show their wares. In the continuing discussions on the topic, they expected 10 or so producers to show up for the inaugural event but over 30 did. The first two sessions were almost big parties, according to Brandon. This fair was held at Franchetti's estate for a while before moving elsewhere.

In Conclusion

Andrea's legacy is clear. He built two high-quality estates in two very different regions with differing grape varieties and grape-growing environments, all without the presence of a regional support system. He went into the Val d'Orcia boondocks and designed and built an enterprise that today produces some of the best Bordeaux-style wines coming out of Tuscany. He had no Consorzio to lean on for assistance. He had no surrounding collegial producers. Such an infrastructure does not even exist in the area to this day.

A similar situation existed at the time he came to Mt. Etna in that, even though the region had historical wine roots, with the exception of Benanti there were few high quality wine producers. Franchetti brought his Trinoro style to Etna but realized pretty quickly that the formula was inapplicable there and made the adjustments necessary to produce a high-quality wine.

How has Franchetti contributed to the shaping of the wine direction on Etna? First, he was part of the initial group of outside investors who brought the potential of this region to the eyes of the wider world. Second, he showed that a Bordeaux cultivar (Petit Verdot) could be blended with an almost extinct cultivar (Cesanese d'Affile) to make a world-class, non-indigenous wine on the mountain. Third, his focus on the importance of contrada effects, both in the stable of wines that he produced and in his establishment and support of Contrada dell"Etna.

One of the questions that will begin to boil to the surface in short order is "what's next?" There is always some concern as to how a wine brand will be affected by the passing of its founder and history is replete with both positive and negative examples. What is especially interesting here is that Andrea stood athwart two enterprises and it is not obvious that there is any other person possessing that vantage point. Both estates are equipped with highly competent operational management so there will be no problem in that regards. The areas where some differences could potentially emerge are in the knowledge of the vineyards and picking decisions. Andrea roamed the fields incessantly and alone. His picking decisions were made based on his intimate knowledge of those vines. His ideas for brand extensions came about through his knowledge of the evolution of those vines. We will all wait with bated breath and continued good wishes for the employees, management, and customers of Vini Franchetti.

©Wine --

Mise en abyme