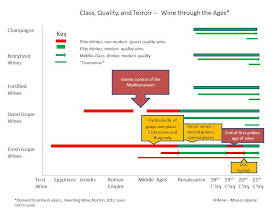

As illustrated in my graphical summation of the history of wine styles -- described in Lukacs' Inventing Wine: A New History of one of the World's Most Ancient Pleasures -- the next significant development in wine after the Fall of Rome is place-based wines out of Burgundy. According to Lukacs, the "first wines prized for their ability to display ... individualized aroma and flavors" were made in Burgundy by the Cistercian order which had been founded in 1098. This order was focused on piety and hard work and devoted a lot of effort to tending their vineyards. In his APAVM FAW lecture (titled St. Benedict and the Blessings of Burgundy), Dr. Jonathon Britto provided insight into events leading up to and surrounding the Cistercians and Burgundian wine.

Gregory of Tours was a prelate, historian, and chronicler who "resided at the junction of Rome of antiquity and the emergence of the medieval world" and "documented the continuity of Gallo-Roman civic culture through the early Middle Ages." This Gregory was the first to sound the praises of the wines of Burgundy in a 591 writing. According to Dr. Britto, King Guntrum of Burgundy had donated land to the monks in 587.

|

| Gregory of Tours |

Saint Benedict established "the Rules," which became the governing principles of monastic life. The Rules provided for a balance of prayer, work, and study. Charlemagne was enamored and had them copied and distributed throughout his realm in the 8th and early 9th centuries in order to encourage monks to adopt the principles. Saint Benedict's Rules, according to Dr. Britto, "laid the groundwork for community discipline of labor and this ethic, plus the donation of fertile land for the growing of grapes, was the kernel for successful viticulture in Burgundy.

|

| St. Benedict (Portrait (1926)) Herman Nieg (1849–1928); Heiligenkreuz Abbey, Austria |

The Benedictine Abbey of Cluny was founded in 910 by Duke William I of Aquitaine and was given to the monks "untethered." The deed of gift "included vineyards, fields, meadows, woods, waters, mills, serfs, and lands (cultivated and uncultivated)."

The Abbey started out on a modest scale, but at its peak was home to 1,000 monks and seeded monastic life throughout Europe. Such a large contingent of monks required administration, fields, and food and was financed partly through indulgences and partly through wine trade. The Benedictines became major landowners with holdings in Gevrey-Chambertin and Vosne-Romanee in Burgundy plus holdings in Rhone, Champagne, and the Loire Valley.

When completed in the early 12th century, the Abbey was the largest church in Christendom and remained the largest building in Europe until the 16th-century completion of the new St. Peter's in Rome. Cluny was plundered and destroyed during the French Revolution.

While, on the face of it, Cluny was a success, a number of resident monks felt that monastic life had been "challenged and traded for a commercial life." These "conservatives" felt that the only way to resolve their internal conflict was to leave Cluny and return to a stricter observance of the Christian monastic tradition.

In 1075, Robert Moleme was given permission by Pope Gregory to leave Cluny and establish his own Abbey. Robert de Moleme and his monks acquired a plot of marshland south of Dijon at a place called Citeaux and set up an Abbey as the seat of a new Cistercian Order. The Citeaux monks returned to the original Benedictine ideals of manual work and prayer, dedicating themselves to charity and self-sustenance.

Robert was called back to Cluny and left the Abbey in the hands of Steven Harding, and Anglo-Saxon who had lost his holdings during the course of the Norman invasion. He was elected Abbot and led the Cistercian community ably. The Cistercians grew, "forging alliances with the Duke of Burgundy and, by both donation and purchase, acquired vineyards in Meursault and Clos Vougeot." They eventually encircled Vougeot with the wall that stands to this day. The wall was completed at the end of the 15th century.

Harding was a prolific recorder of contemporary events and wrote that the Cistercians were the first to notice that different vineyard plots gave different wines consistently. According to Lukacs, over the course of many vintages, these monks were able to identify the characteristics of individual vineyard plots and to note that these differences were, in some cases, manifested by "only a few steps separating an excellent grape-growing spot from a merely good one." The monks marked out these plots by their differences, in some cases building a stone wall to create a "cloistered vineyard."

Lukacs takes the position that the monks did not intend that their demarcations single out one vineyard as better than the other. Rather, they were saying that the grapes sourced from these vineyards made reliably noticeably different wines and they thus needed to be so identified. The wines from Clos Vougeot and other Cistercian crus were perceived as being so different as to be worth the trouble and expense of overland shipping to the relevant markets or waterways for onward transit.

Dr. Britto: The Cistercians therefore "laid the first foundation for labeling the Burgundy cru and the region's terroir philosophy. It was the Cistercians who defined every tiny parcel of vineyard land, identified the good and the bad points, the geology and micro-climate, and the different flavors and yields.

The diligence inherent in the Benedictine rules, and the application of the work ethic, were instrumental in the identification and mapping of the Burgundian crus that we know today.

No comments:

Post a Comment