But these high-minded ideals dissipate quickly as, in the Introduction, beginning on the following page, Ms. Legeron initiates a takedown of modernity with the following statement: "The 20th century changed the face of modern agriculture. It streamlined, mechanized, and 'simplified' farming in an attempt to increase yields and maximize short-term profits." Ms. Legeron continues in this vein for the rest of the Introduction eventually covering the slate of issues summarized in the below graphic. Further, on page 14, "And what is extraordinary is that most of the of this change has happened over the last 50-odd years.

So taking Ms. Legeron at her word, things were fine prior to 50 years ago when science reared its ugly head and began to spoil things for every one.

But, looking through the lens of history, Lukacs (Inventing Wine) paints a different picture of the roles of human control and science in the construction of the wine industry that we know today. According to Lukacs,

At the end of the Second World War, a veteran grape grower in virtually any European country could look back over a lifetime of long, hard toil and remember little more than trouble, years marked by deceased vineyards, financial collapse, commerce filled with fraud and horribly violent conflict.Further, consumers were not drinking wine any more because municipal water was now safe and clean and refrigeration allowed milk and other perishable beverages to be distributed widely. The social drink of choice was a cocktail. The wine industry, such as it was, needed to revitalize itself. And that it did. Again Lukacs:

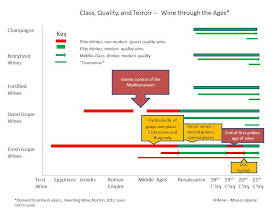

From expressing terroir in the vineyard, to employing new technology in order to attain consistency in the winery and stability in the bottle, the potential intimated during wine's initial modernization began to be achieved on an astonishingly broad scale ... Starting slowly in the 1950s and 1960s, but then quickly gaining momentum in the following decades, the quality of not just exclusive, expensive cuvees but also widely available and moderately priced wines rose to previously unimagined heights.Just to step back a little into the history of wine, as the figures below show, it is not until the advent of the French AOC system in the early 1930s that the wine available to everyday individuals attained some modicum of quality. And then came the Second World War, and with it, a reversion to the past.

Lukacs points out that winemaking in the first half of the 20th century was a reprise of thousands of years past -- "a process of letting nature run its course." But beginning in the 1950s and 1960s grape growers and winemakers began to employ new tools to attain specific "stylistic and qualitative ends." On the technical side, the introduction of temperature control and regular chemical analysis allowed greater control over the fermentation and this gave greater impetus to the concept that humans "could and should assume control" of the winemaking process.

The concept of human control of the winemaking process was not new, according to Lukacs. It began with Enlightenment scientists such as Antoine Lavoisier and Jean-Antoine-Claude Chaptal in the 1700s, continued through Pasteur (with his discoveries of the role of yeasts and bacteria in fermentation and spoilage) and the work of Emile Peynaud, both in his lab and working with the Bordeaux Chateaus to convert his research to actionable inputs into the winemaking process. Peynaud's contribution included refrigeration, understanding the role of malolactic fermentation, and the need for rigorous selection in the vineyard. His efforts changed the stylistic and qualitative character of the Bordeaux wines such that the "whites became less tart and vegetal and the reds more supple and sensuous, fuller in flavor but less astringent."

"By the second half of the century, the basic idea of directing and mastering winemaking had become so commonplace as to be unquestioned." According to the Director (Pascal Ribereau-Gayon) of the Institute where Peynaud worked, "... great gifts are not just gifts of nature but 'the fruit of a discipline imposed by man upon nature.' "

When Peynaud began his work in the early 1950s, growers were harvesting early and,as a result, the wines were "excessively green or vegetal." He observed that there was a further striking uniformity about the wines: they were all oxidized. Is this the future that Ms. Legeron would prefer that we have? While I can agree with her on the need for better treatment of our soils, and the reduced usage of pesticides, herbicides and nutrients therein (primarily because of their externalities), a wholesale indictment of science in winemaking, and man's attempt to understand and control the relevant processes, is both shortsighted and ungrateful based on the lessons of history.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

No comments:

Post a Comment