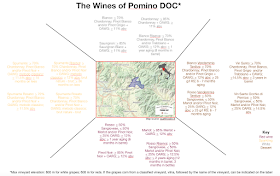

Dong, et al., reports on a dispersal of the vitis vinifera CG1 cultivar in four directions from its domestication point in western Asia, as illustrated in the map below.

|

| High-Level view of the early stages of vitis vinifera distribution from the Western Asia Domestication Center (after Dong, et al.) |

I have previously detailed hypotheses as to how the cultivar spread into Anatolia and across Europe and North Africa, with reports on the Caucasus and the Far East in the offing. Before addressing the latter endpoints, however, I will cover the evidence of transit through Iran, the point of divergence for the cultivar's onward journeys.

According to the authors, the dual domestications occurred 11,000 years ago. The Little Ice Age had ended by this time and the world was transitioning from the Pleistocene to the Holocene Epoch.

The cold, dry climate associated with the Younger Dryas (12,800 BP - 11,600 BP) led to a rapid reduction in the size of the lushest vegetation belts and reduction in yields of natural stands of C3 plants such as cereals.

There was rapid return of wetter weather post the Younger Dryas and this led to the expansion of numerous lakes and ponds and cultivation of annual crops along the shorelines. The first large villages began to appear (up to 2.5 ha) and they relied on cultivated barley and wheat or "their wild progenitors."

Neolithic farming communities thrived under the favorable climate conditions of the Early Holocene and expanded "along the Levantine Corridor into Anatolia and neighboring regions." This, then, was the first movement of the cultivated grapevine outside of its birthplace.

Post-Younger-Dryas warming took 1000 years to reach Iran and another 1000 years to reach the heart of Central Asia. Cereal grasses and trees followed the path of this warming; as did agriculture. The Neolithic -- the period of the origins and early development of agricultural economies -- launched in the Levant around 11,000 years ago and was evident in Iran during the period 10,000 BP - 7500 BP.

Within Iran, Neolithisation did not occur in one fell swoop. Rather, it was evidenced as "a gradual unfolding of multiple episodes of Neolithisation producing patterns of change, continuity and adaptation over several millenia." The chart below illustrates the unfolding of Neolithisation in Iran.

Human groups in Iran's Zagros Mountains developed autonomously -- in relation to the Levant -- during the beginning of the Holocene, with local domestication of goats and early stage agriculture based on barley. The material culture has been confirmed by DNA studies which show that humans from the Zagros and Levant were "strongly differentiated genetically and were each descended from local hunter-gatherers."

There were a number of core areas that were "large enough to have fostered distinct and thriving societies throughout the Neolithic and beyond":

- Northern, central, and southern Zagros

- Khuzistan lowland

- Southern Iran

- Northeastern Kopet Dag

Of the above, the Khuzistan lowland has "the longest continuous sequence of Neolithic occupation" and the "oldest substantial evidence for agriculture and animal husbandry in Iran." Given our assertion of a nexus between the adoption of agriculture and the adoption of grape cultivation, and the proximity of Khuzistan to the Fertile Crescent, it is quite likely that grape vines were cultivated in Khuzistan at some time in the Neolithic. And that assertion is bolstered by archaeological findings at Hajji Firuj, a Northern Zagros archaeological site which was occupied between 7900 and 7500 BP.

Hajji Firuz was a small village of single-family dwellings with an economy based on a mix of farming and herding, with the latter potentially requiring seasonal migration. The dates of occupation suggest that agriculture and herding at this location was relatively late when compared to Central Zagros and the Khuzistan lowlands. The location of the site is illustrated on the map below.

|

| Red oval highlights archaeological sites where proof of winemaking in ancient Iran (Persia) was unearthed. |

Hajji Firuz Tepe was the subject of an archaeological excavation in 1968 at which five 2.5 gallon (9 liter) jars were found embedded in an earthen floor along a wall of a Neolithic mud brick building. Two of these jars had a yellowish residue on the bottom which, after being subjected to infrared liquid chromatography and wet chemical analysis, proved to be a combination of calcium tartrate and terebinth tree resin. Tartaric acid in the amounts found can only be associated with grapes and the amount of wine that would be housed in the five containers would be much more than required for a single family's use. Clay stoppers that perfectly fit the openings at the top of the clay jars were found in close proximity to the jars and was assumed to have been used to prevent the contents from turning to vinegar. These factors led the archaeologists to tag this site as a wine-production facility -- playfully called "Chateau" Hajji Firuz by Dr. McGovern. As wines in Greece even today are resinated, the assumption is that resin was added to Neolithic wines either as a preservative or for medicinal purposes.

|

| Jar from Hajji Firuz Tepe (Source: alaintruong.com) |

The work done by the McGovern team clearly shows the use/consumption of wine within Neolithic Iran. Given that the domestication of vitis vinifera fell within the bounds of the Fertile Crescent, and that the southwestern part of Iran also fell within the bounds of that construct, its transit route into Iran becomes clearer.

Pottery-making in Iran has a history dating back to the early 7th millennium with the advent of agriculture giving rise to the baking of clay and the making of utensils. The use of clay jars for the storage of wine at Hajji Firuz Tepe is, therefore, a temporal fit.

From Iran, vitis vinifera CG1 made its way to the Caucasus and Central Asia. I will cover the former in my next post on the topic.

Bibliography

Saffaid Alibaigi and A. Salomiyan, The Archaeological landscape of the Neolithic period in the western foothills of the Zagros Mountains: New evidence for the Sar Pol-Ezahāb region, Iraq - Iran Borderland, Iraq, Vol 82, Cambridge University Press, December 2020.

Oliver Barge, et al., Diffusion of Anatolian and Caucasian Obsidian in the Zagros Mountains and the highlands of Iran: Elements of Explanation in 'leastcost path' models, Quaternary International 467 (Part B), February 2018.

Dong, et al., Dual domestications and origin of traits in grapevine evolution, Science, 3/3/23

Encyclopedia Iranica, Neolithic age in Iran.