Today I read a confusing (for me) and somewhat disingenuously titled article on wine-searcher.com called "The Reality of Minerality." Having written extensively on the topic on this blog, I was intensely interested and clicked through thinking that I had missed some grand development that had cleared up this abiding mystery once and for all. It was not what it appeared to be. As a matter of fact, I have some issues with the article and the report on which it is based; at least the elements of the report that are shared in this article.

The article was reporting on a study whose objective was to use trained sensory judges in New Zealand and France to investigate cultural differences in the perception of minerality," with the cultural differences arising around Sauvignon Blanc production processes and style. According to the wine-searcher article, the "results suggest that the concept is very real." Note that we have gone from the definitive "reality of minerality" in the title to the "concept" here. Further, a "concept" is defined as a "general idea or understanding" while "real" is defined as "being or occurring as fact" or "having verifiable existence." Is the author suggesting here that the idea of minerality is a verifiable fact? Because that is inaccurate. The traditional idea of minerality in wine revolves around the idea that minerals from the ground are somehow absorbed into the vine, transported into the fruit, and survives the rigors of fermentation to present "itself" unscathed to the taster's palate. And, being from the Maltman school, I do not buy that.

The lead author on the underlying study is quoted in the article as saying "Lack of perceived flavor was associated with the perception of minerality ... If there was nothing much else in the wine, people resort to calling it mineral by a process of elimination." This is not an argument for minerality; this is an argument against lack of flavor in wines and posits a fallback position for tasters: "If I cannot check any other box, let me check mineral." As a matter of fact, this is the headline here: "The perception of minerality results from an absence of detectable/describable flavors in wine." I can see the big-time tasters buying-in to that concept.

And maybe the issue here is the word minerality. We know that minerals cannot be smelled or tasted so why do we persist in acting as though we can taste and smell minerals in our wine. I am willing to concede that there is some sensation that I experience when I drink some white wines that is not adequately described by the available population of descriptors. But minerality is too loaded. Perminality anyone.

The article closes with the lead author stating "We are still not sure what minerality is." You probably should not be saying that in an article titled "The Reality of Minerality."

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Pages

▼

Tuesday, March 31, 2015

Monday, March 30, 2015

Iconic Swiss Varietals Tasting with Paolo Basso: Brivio Vini Platinum 2011 Mendrisio AOC Tessin

Paolo Basso has consistently been one of the world's best sommeliers and has two World's Best Sommelier awards (2010 and 2013) as official recognition of that standing. I had never had the opportunity to meet him, or attend one of his tastings, so I jumped at the opportunity to register for an event titled Iconic Swiss Varietals Tasting that he would be hosting at the DWWC 2014 Conference in Montreux, Switzerland. This post continues my reporting on that event with coverage of the Brivio Vini Platinum 2011 AOC Tessin. Previous entries in this series are listed at the end of this post.

Ticino -- called Tessin in both French and German -- is a 2,813-km² (1,086 square-mile) Swiss canton located on the southern slopes of the central Alps. Italian-speaking (an artifact of rule by the Dukes of Milan until its conquest by the Swiss Confederation in the 15th Century), except for the German-speaking municipality of Bosco/Gurin, the canton is almost completely surrounded by Italy.

The canton is divided into two geographic regions by the dividing line of the Monte Ceneri Pass: Sopraceneri, encompassing the Ticino and Maggia Valleys; and Sottoceneri, the region around Lake Lugano. The Sopraceneri lands were formed by glaciers and streams and, as a result, are more mountainous and rife with terminal moraines and alluvial cones and is acidic. The soils are rather stony with a full complement of silt and sand. The Sottoceneri soils are limestone and deep, rich clays.

Ticino's climate has been described as "modified Mediterranean." The Alps in general, acts as a barrier such that the climate in the northern parts of Switzerland are different from the south. Ticino, situated as it is to the south of the Alps, receives some Mediterranean air from time to time and can reach temperatures of 21.3℃ in the summer with an average annual temperature of 11.7℃. Ticino's 2100-2286 hours of sunshine per year is the highest in Switzerland. The warm, moisture-laden air from the Mediterranean deposits a lot of its mass as it rises to soar over the Alps, leaving Ticino with the highest annual rainfall (1750 mm) in all of Switzerland. The Froehm is a warm wind which blows over the Alps from south to north but, on occasion, reverses itself and blows from north to south, impacting Ticino. Ticino is prone to fierce storms and the risk of hailstones has prompted grape-growers to install anti-hailstone nets.

Platinum is produced by Brivio Vini SA which operates as a negociant with production facilities in Mendrisio. Brivio Vini buys fruit from 400 farmers operating on 100 ha of land in the region. The table directly below shows DOC labels produced by this winery; 10 of the 13 wines are 100% Merlot or has Merlot as part of the blend. The figure below the table illustrates the Brivio winemaking process.

Distribution of Brivio Wines by Type and DOC

*One except stated otherwise

Platinum is a 100% Merlot wine. Brivio works with a low-yield clone to realize yields of 50 hl/ha. The grapes for this wine are dried for three weeks in thermo-ventilated boxes before alcoholic fermentation begins (This practice increases the solids concentration in the grape prior to alcoholic fermentation but may do so at the expense of freshness.). The grapes are then crushed and fermented in temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks. After fermentation and MLF, the wine is aged for 20 months in new French oak barriques. Frequent racking during this period allows bottling without fining or filtration. The producer does allow that this practice may result in some slight visible sedimentation.

As tasted, the wine presented balsamic notes, vanilla, and baking spices on the nose. Overripe fruit with a dusky nature. Fruity, black cherry, black currant, and ivy leaf (Paolo sees the latter as a typical aroma of the region). On the palate black fruits. Rich and concentrated. Full-bodied. Young tannins providing some astringency. Long, rich finish.

**********************************************************************************************************

Previous Iconic Swiss Varietals Tasting posts:

Leyvraz St-Saphorin Grand Cru Les Blassinges 2012

St-Jodern Kellerei Visperterminen Veritas Heida 2012 AOC Valais

Jean-René Germanier Vétroz Cayas Syrah du Valais Réserve 2009

Clos de Tsampéhro Flanthey Tsampéhro Rouge Edition I 2011 AOC Valais

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Ticino -- called Tessin in both French and German -- is a 2,813-km² (1,086 square-mile) Swiss canton located on the southern slopes of the central Alps. Italian-speaking (an artifact of rule by the Dukes of Milan until its conquest by the Swiss Confederation in the 15th Century), except for the German-speaking municipality of Bosco/Gurin, the canton is almost completely surrounded by Italy.

|

| Source: wineandvinesearch.com |

The canton is divided into two geographic regions by the dividing line of the Monte Ceneri Pass: Sopraceneri, encompassing the Ticino and Maggia Valleys; and Sottoceneri, the region around Lake Lugano. The Sopraceneri lands were formed by glaciers and streams and, as a result, are more mountainous and rife with terminal moraines and alluvial cones and is acidic. The soils are rather stony with a full complement of silt and sand. The Sottoceneri soils are limestone and deep, rich clays.

Ticino's climate has been described as "modified Mediterranean." The Alps in general, acts as a barrier such that the climate in the northern parts of Switzerland are different from the south. Ticino, situated as it is to the south of the Alps, receives some Mediterranean air from time to time and can reach temperatures of 21.3℃ in the summer with an average annual temperature of 11.7℃. Ticino's 2100-2286 hours of sunshine per year is the highest in Switzerland. The warm, moisture-laden air from the Mediterranean deposits a lot of its mass as it rises to soar over the Alps, leaving Ticino with the highest annual rainfall (1750 mm) in all of Switzerland. The Froehm is a warm wind which blows over the Alps from south to north but, on occasion, reverses itself and blows from north to south, impacting Ticino. Ticino is prone to fierce storms and the risk of hailstones has prompted grape-growers to install anti-hailstone nets.

Platinum is produced by Brivio Vini SA which operates as a negociant with production facilities in Mendrisio. Brivio Vini buys fruit from 400 farmers operating on 100 ha of land in the region. The table directly below shows DOC labels produced by this winery; 10 of the 13 wines are 100% Merlot or has Merlot as part of the blend. The figure below the table illustrates the Brivio winemaking process.

Distribution of Brivio Wines by Type and DOC

Type

|

DOC

|

# *

|

Chardonnay

|

Semillon

|

Pinot Noir

|

Sauv Blanc

|

Merlot

|

Gamaret

|

Cab Franc

|

Cab Sauv

|

White

|

Bianco del Ticino

|

40%

|

25%

|

20%

|

15%

| |||||

Bianco di Merlot

|

2

|

100%

| ||||||||

Sauvignon

|

100%

| |||||||||

Chardonnay

|

100%

| |||||||||

Rosé

|

Rosato di Merlot

|

100%

| ||||||||

Red

|

Merlot

|

6

|

100%

| |||||||

Rosso di Ticino

|

2

|

34%

65%

|

60%

|

8%

|

27%

|

Platinum is a 100% Merlot wine. Brivio works with a low-yield clone to realize yields of 50 hl/ha. The grapes for this wine are dried for three weeks in thermo-ventilated boxes before alcoholic fermentation begins (This practice increases the solids concentration in the grape prior to alcoholic fermentation but may do so at the expense of freshness.). The grapes are then crushed and fermented in temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks. After fermentation and MLF, the wine is aged for 20 months in new French oak barriques. Frequent racking during this period allows bottling without fining or filtration. The producer does allow that this practice may result in some slight visible sedimentation.

As tasted, the wine presented balsamic notes, vanilla, and baking spices on the nose. Overripe fruit with a dusky nature. Fruity, black cherry, black currant, and ivy leaf (Paolo sees the latter as a typical aroma of the region). On the palate black fruits. Rich and concentrated. Full-bodied. Young tannins providing some astringency. Long, rich finish.

**********************************************************************************************************

Previous Iconic Swiss Varietals Tasting posts:

Leyvraz St-Saphorin Grand Cru Les Blassinges 2012

St-Jodern Kellerei Visperterminen Veritas Heida 2012 AOC Valais

Jean-René Germanier Vétroz Cayas Syrah du Valais Réserve 2009

Clos de Tsampéhro Flanthey Tsampéhro Rouge Edition I 2011 AOC Valais

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Wednesday, March 25, 2015

Lunch with Jean-Marc Roulot and Christophe Roumier at Daniel: La Paulee NYC

The main event of La Paulée's official Thursday afternoon schedule was a multi-course lunch, prepared by Daniel Boulud and his team, accompanied by selected wines from Domaines Guy Roulot and Georges Roumier, said wines to be presented by the respective vigneron. At the conclusion of the Roulot play, lunch attendees were shepherded back towards the front of the restaurant and into a room to the right of the main entrance. The room was populated with a number of 10-top, white-table-cloth-clad tables and as we entered, we were given additional glasses of Meursault Les Luchets 2011. As the attendees streamed in, I was pleasantly surprised to see Aubert de Villaine enter and stride to a place at the Roulot-Roumier table which was centrally located within the room. Daniel Johnnes welcomed us all and then launched the event.

The first course was called Jaune d'or et Soleil Vivace (components were Iberico Ham, truffles, and eggs) and had been prepared by Michel and César Troisgrois.

It was accompanied by 2010, 2009, and 2004 Roulot Les Luchets, the former two in magnum. The 2010 Les Luchets exhibited spice, orange-tangerine, power, minerality, orange rind, burnt orange and a slight pricking on the nose. On the palate bright, powerful, intense. Long, intense finish. The 2009 Les Luchets had similar characteristics to the 2010 except it had a little more stemminess, was a little more aromatic, and showed riper fruit. It was also not as tightly wound as the 2004. The 2004 exhibited a lemon-lime aroma along with minerality, crushed stone, sea shells and a hint of sulfur. Slight salinity and great acidity. Balanced. Bright, long, coating finish.

The second course was a Filet de Sole Duglére also prepared by Michel and César Troisgros. This was accompanied by a Roulot Meursault Charmes 2004, Roulot Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir 2000 (in Jeroboam) and Roulot Meursault Perrières 1999 (in magnum).

The Meursault Charmes 2004 had tangerine and orange rind citrus characters accompanying notes of spice and herbs. Voluptuous, with bracing acidity and a long finish. The 2000 Meursault Tessons was elegant with apple-pear notes, spice, herbs, cardamom. The 1999 Meursault Perrières had citrus and citrus rind on the nose. Powereful, mineral, and coating on the palate.

The third course was a Bœuf Wagyu Rossini which was prepared by Daniel Boulud. And this signaled a turn to the wines of Domaine Georges Roumier. The wines that he presented were the Domaine Georges Roumier Bonnes-Mares 1996, 1995, and 1990, all in magnums.

Bonnes Mares is a 15.06 ha Grand Cru appellation that sits at the northern end of Chambolle-Musigny and hosts 22 producers, one of whom is Domaine Georges Roumier with its 1.39 ha distributed over four plots. According to Clive Coates (www.clive-coates.com), the vineyard lies between 270 and 300 meters altitude and is comprised of two soil types -- terres blanches (a white marl rich in fossilized oysters) and terres rouges (red-brown soil possessing more clay) -- each yielding a different wine style from the same grape. Domaine Georges Roumier has vines on both these soil types and ferments the wines separately, blending them at a later date.

The Domaine Roumier Bonnes Mares Grand Cru 1996 exhibited ripe pinot fruit, a herbaceousness, and barrel spice on the nose. Restrained but balanced. Long, spicy finish. The 1995 Bonnes-Mares had a richer nose than the 1996, and greater power and intensity. The 1990 Bonnes-Mares showed pinot fruit, spice, and orange peel on the nose. Perfect weight on the palate. Balanced. Light stemminess/astringency. Herb finish.

Thus culminated an absolutely wonderful day. You do not get this type of variety thrown at you in the wine world every day. Especially in NYC, you can go to a play any day of the week. But it is not every day of the week that you get to see one of the leading winemakers from the famously tight-lipped and closeted region of Burgundy placing his reputation on the line by stepping on stage in front of his customers and running the risk of hurting his brand. And it is not every day that you get to follow that up with that same guy coming back and pouring you a range of his best wines. And, for good measure, he invited along one of his friends to pour some of his (the friend's wines). And all that wrapped around the food of Master Boulud.

It does not get any better than this.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

The first course was called Jaune d'or et Soleil Vivace (components were Iberico Ham, truffles, and eggs) and had been prepared by Michel and César Troisgrois.

It was accompanied by 2010, 2009, and 2004 Roulot Les Luchets, the former two in magnum. The 2010 Les Luchets exhibited spice, orange-tangerine, power, minerality, orange rind, burnt orange and a slight pricking on the nose. On the palate bright, powerful, intense. Long, intense finish. The 2009 Les Luchets had similar characteristics to the 2010 except it had a little more stemminess, was a little more aromatic, and showed riper fruit. It was also not as tightly wound as the 2004. The 2004 exhibited a lemon-lime aroma along with minerality, crushed stone, sea shells and a hint of sulfur. Slight salinity and great acidity. Balanced. Bright, long, coating finish.

The second course was a Filet de Sole Duglére also prepared by Michel and César Troisgros. This was accompanied by a Roulot Meursault Charmes 2004, Roulot Meursault Tessons Clos de Mon Plaisir 2000 (in Jeroboam) and Roulot Meursault Perrières 1999 (in magnum).

The Meursault Charmes 2004 had tangerine and orange rind citrus characters accompanying notes of spice and herbs. Voluptuous, with bracing acidity and a long finish. The 2000 Meursault Tessons was elegant with apple-pear notes, spice, herbs, cardamom. The 1999 Meursault Perrières had citrus and citrus rind on the nose. Powereful, mineral, and coating on the palate.

|

| de Villaine and Roulot |

|

| Daniel Johnnes with the Jeroboam of Tessons |

The third course was a Bœuf Wagyu Rossini which was prepared by Daniel Boulud. And this signaled a turn to the wines of Domaine Georges Roumier. The wines that he presented were the Domaine Georges Roumier Bonnes-Mares 1996, 1995, and 1990, all in magnums.

Bonnes Mares is a 15.06 ha Grand Cru appellation that sits at the northern end of Chambolle-Musigny and hosts 22 producers, one of whom is Domaine Georges Roumier with its 1.39 ha distributed over four plots. According to Clive Coates (www.clive-coates.com), the vineyard lies between 270 and 300 meters altitude and is comprised of two soil types -- terres blanches (a white marl rich in fossilized oysters) and terres rouges (red-brown soil possessing more clay) -- each yielding a different wine style from the same grape. Domaine Georges Roumier has vines on both these soil types and ferments the wines separately, blending them at a later date.

The Domaine Roumier Bonnes Mares Grand Cru 1996 exhibited ripe pinot fruit, a herbaceousness, and barrel spice on the nose. Restrained but balanced. Long, spicy finish. The 1995 Bonnes-Mares had a richer nose than the 1996, and greater power and intensity. The 1990 Bonnes-Mares showed pinot fruit, spice, and orange peel on the nose. Perfect weight on the palate. Balanced. Light stemminess/astringency. Herb finish.

|

| Poire Tahitienne (Daniel Boulud) |

Thus culminated an absolutely wonderful day. You do not get this type of variety thrown at you in the wine world every day. Especially in NYC, you can go to a play any day of the week. But it is not every day of the week that you get to see one of the leading winemakers from the famously tight-lipped and closeted region of Burgundy placing his reputation on the line by stepping on stage in front of his customers and running the risk of hurting his brand. And it is not every day that you get to follow that up with that same guy coming back and pouring you a range of his best wines. And, for good measure, he invited along one of his friends to pour some of his (the friend's wines). And all that wrapped around the food of Master Boulud.

It does not get any better than this.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Tuesday, March 24, 2015

Christophe Roumier of Domaine Georges Roumier

The Jean-Marc Roulot play was the opening salvo in a double-header of elevated -- and elevating -- experiences that were visited on La Paulée participants who attended the Daniel event on Thursday afternoon. The main event was scheduled to be a multi-course lunch, prepared by Daniel Boulud and his team, accompanied by selected wines from Domaines Guy Roulot and Georges Roumier, said wines to be presented by the respective vigneron. Readers of this blog are familiar with Jean-Marc Roulot and his domaine but have never been exposed to Christophe Roumier herein. In that I believe that context aids in appreciation/understanding of a wine, this post sheds some light on the vigneron and his domaine.

Christophe and his wines are widely acclaimed. Writing on his blog (Roumier, www.clive-coates.com), Clive Coates states thusly: "For Chambolles with a difference, wines which are substantial, even sturdy, as well as elegant and velvety, the best source is ... the Domaine Georges Roumier. This is one of the longest estate bottling domaines in the Côte D'Or. And one of the very best of all." Jonathon Nossiter (Liquid Memory) described Roumier as "one of the poster children of the new generation of Burgundian vignerons ... who not only make biodynamic, organic, or chemical-free wines from the greatest terroirs in Burgundy ... but have outstripped the parents in quality, sophistication, and renown and yet they have all maintained their peasant rootedness and commitment to an ever more precise expression of terroir."

The domaine was founded in 1924 by Georges Roumier and was one of the early adopters of the practice of in-house bottling. Georges began to transition the estate to his son Jean-Marie in the 1950s but did not fully retire until 1961. In the same fashion, Jean-Marie began a transition to Christophe -- who had joined him in 1982 -- which culminated in a total handoff in 1990.

Most of the 11 ha of land from which the domaine sources its grapes is rented from family members. The exception is Ruchottes-Chambertin which is worked in a sharecropping arrangement with the proprietor, one Michel Bonnafond. The distribution of Roumier fruit sources is as shown below.

The domaine's vines are farmed biodynamically and are known for low yields. The grapes are sorted in the vineyard and then transported to the cellar where they are mostly de-stemmed before being placed in wooden open-topped fermenters. The must is cold soaked at 15℃ before the initiation of an approximately 3-week fermentation by indigenous yeasts. The cap is punched down twice daily to ensure optimal extraction of flavor, anthocyanin, and tannin compounds.

After fermentation the wines are racked off into barriques for malolactic fermentation and aging. The oak regime is as follows:

Now that we have dotted all I's and crossed all T's, we can turn to the main event: Lunch with Jean-Marc Roulot and Christophe Roumier.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Christophe and his wines are widely acclaimed. Writing on his blog (Roumier, www.clive-coates.com), Clive Coates states thusly: "For Chambolles with a difference, wines which are substantial, even sturdy, as well as elegant and velvety, the best source is ... the Domaine Georges Roumier. This is one of the longest estate bottling domaines in the Côte D'Or. And one of the very best of all." Jonathon Nossiter (Liquid Memory) described Roumier as "one of the poster children of the new generation of Burgundian vignerons ... who not only make biodynamic, organic, or chemical-free wines from the greatest terroirs in Burgundy ... but have outstripped the parents in quality, sophistication, and renown and yet they have all maintained their peasant rootedness and commitment to an ever more precise expression of terroir."

|

| Christophe Roumier and Ron at La Paulée (Photo courtesy Ron Siegel) |

The domaine was founded in 1924 by Georges Roumier and was one of the early adopters of the practice of in-house bottling. Georges began to transition the estate to his son Jean-Marie in the 1950s but did not fully retire until 1961. In the same fashion, Jean-Marie began a transition to Christophe -- who had joined him in 1982 -- which culminated in a total handoff in 1990.

Most of the 11 ha of land from which the domaine sources its grapes is rented from family members. The exception is Ruchottes-Chambertin which is worked in a sharecropping arrangement with the proprietor, one Michel Bonnafond. The distribution of Roumier fruit sources is as shown below.

- Grands Crus

- Corton-Charlemagne -- 0.2 ha

- Musigny -- 0.1 ha

- Bonnes-Mares -- 1.6 ha

- Ruchottes-Chambertin -- 0.54 ha

- Charmes-Chambertin -- 0.28 ha

- Premiers Crus

- Clos de la Bussière -- 2.59 ha

- Les Amoureuses -- 0.4 ha

- Les Cras -- 1.75 ha

- Combottes -- 0.27 ha

- Village

- Chambolle-Musigny -- 3.70 ha

The domaine's vines are farmed biodynamically and are known for low yields. The grapes are sorted in the vineyard and then transported to the cellar where they are mostly de-stemmed before being placed in wooden open-topped fermenters. The must is cold soaked at 15℃ before the initiation of an approximately 3-week fermentation by indigenous yeasts. The cap is punched down twice daily to ensure optimal extraction of flavor, anthocyanin, and tannin compounds.

After fermentation the wines are racked off into barriques for malolactic fermentation and aging. The oak regime is as follows:

- Village wines -- 15 - 25% new

- Premier Cru and Grand Cru (except Bonnes Mares) -- 25 - 40%

- Bonnes-Mares -- 50%

Now that we have dotted all I's and crossed all T's, we can turn to the main event: Lunch with Jean-Marc Roulot and Christophe Roumier.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Sunday, March 22, 2015

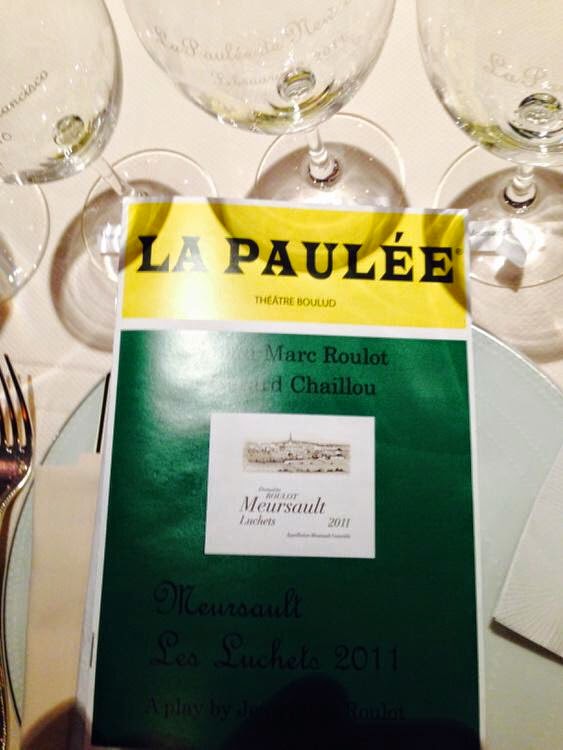

Meursault Les Luchets 2011: A play by Burgundy vigneron Jean-Marc Roulot of Domaine Guy Roulot

Fans of white Burgundy wines know Jean-Marc Roulot as the producer of Meursault wines which have been variously described as "subtly powerful," "feline," and Puligny-Montrachet-like.

But his skills are not bounded by the world of wine. According to Jonathon Nossiter (Liquid Memory), Jean-Marc is an "actor of considerable talent and courage" who entered the prestigious Conservatoir (the French national acting school located in Paris) at the age of 20 and only returned to Burgundy to helm the family Domaine after the premature death of his father.

It was this pedigree, and a fondness for Jean-Marc and his wines, that drove me to sign up to attend his play, and subsequent lunch, which, both held at Daniel, comprised the official Thursday events of the 2015 La Paulée de New York.

The play (the subject of this post) was titled Meursault Les Luchets 2011 and would precede the Roulot-Roumier lunch (For those unfamiliar with the Domaine, Les Luchets is one of its terroirs and wines.). I had not fully recovered from the previous evening's Collectors Dinner with Armand Rousseau because of (i) over-consumption and (ii) I had left my new camera, with my pictures of the night's events, in the back seat of a taxi. And, frantic calls notwithstanding, I had been unable to recover same.

We traveled by taxi from our hotel to Daniel. As I entered the cab, I asked the driver if he had seen my camera. He looked at me as though I had recently been released from a psycho ward. "What camera you talkin' 'bout Bro," he said. "Nothing," I said, my resolve crumbling away as I silently called down the wrath of the heavens on all taxi drivers. Well, enough about my negligence. Let's get back to the matter at hand.

We had gotten to the restaurant pretty close to noon so by the time we had deposited our coats at the coat check (darn NYC winters), checked in, gotten our programs, and were shown to the room, all of the choice seats had been taken. All of the tables in the Daniel backroom had been taken out and chairs had been arranged in an arc around a raised platform set against the rear wall. That rear wall had two openings to a passage that led to who knows where. Towards the front of the stage there was a single wooden table and chair; bare if my recollection serves me well (I had pictures on my iPhone but I lost those when my phone fell into the urinal on Saturday night.). There was an additional chair on the platform stage right and a couch stage left. Stage right, and floor level, was another solitary chair with an accordion on the floor beside it.

We made our way to some open seats house left which gave us a less-than-head-on view of the stage. Shortly after we took our seats, a solitary figure wandered through the opening in the rear wall, sauntered over to the chair associated with the accordion, and began strapping into the instrument. All the while with a bemused smile on his face. According to the program, this was Eric Proud. And he sure acted that way.

Shortly after, another individual made his way onto the stage and sat on the chair stage right. As I was familiar with Jean-Marc, this could only be Gérard Chaillou, who was playing Largeau opposite Jean-Marc's Monplaisir. Finally, Jean-Marc strode onto the stage, an impassive look on his face, staring into the distance. He was carrying a valise which he placed on the table and from which, after rummaging around inside for awhile, he produced a bottle of wine and a corkscrew. While he was opening the wine, Largeau went off stage and returned with two wine glasses into which Jean-Marc poured generous portions. The wines were sniffed and then tasted. And then the dialogue began, each man tapping "into his own language, their words to describe taste linked to their own personal memories and to the sensory world that each and every one of us build and define patiently, year after year" -- Jean-Marc Roulot.

The passion and enthusiasm of the dialogue was captivating, a testament to the skill of the actors as the entire discourse was in French. There was a TV screen high up on the rear wall stage right which displayed subtitled translations of the dialogue but it was tiring -- and tiresome -- to keep switching between the text and the players. A lot was lost in this fashion. Secondly, some of the nuances and subtleties of the situations could not be captured adequately by the subtitled presentation as evidenced by knowing snickers and laughter and expressions of appreciation along the way by French-speaking members of the audience while I sat blank-faced and unknowing.

Sometime during the course of the proceedings Jean-Marc said words akin to "presenting Les Luchets 2011" and, magically, the Somms who were assisting in the event appeared in the glass-walled hallway house right bearing lighted trays with glasses of wine. They stood there momentarily before making their way into the audience and distributing the glasses to the attendees. It was Meursault Luchets 2011. And it was then that I realized what I had been missing all along. I had not had a drink all day.

After all the wine had been distributed, the actors returned to their labors. Including, at one point, a lusty soundtrack in which all three participated.

At the conclusion of the play the attendees showed their appreciation for the actors' efforts with multiple rounds of ovations. It was very revealing to see Jean-Marc in this new environment. I have tasted wine with him at his Domaine and seen him expounding on his wines and engaging in technical discussions with Raj Parr and another US winemaker who had joined us at the tasting. We had enjoyed joyous banter and a bottle of his wine at a chance encounter at Charle Bird's when we went up to NYC for the inaugural La Fete du Champagne. And here he had peeled away those personas, or covered them over with this, the persona of the accomplished, confident, the-world-is-my-oyster actor. I was mesmerized.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

But his skills are not bounded by the world of wine. According to Jonathon Nossiter (Liquid Memory), Jean-Marc is an "actor of considerable talent and courage" who entered the prestigious Conservatoir (the French national acting school located in Paris) at the age of 20 and only returned to Burgundy to helm the family Domaine after the premature death of his father.

It was this pedigree, and a fondness for Jean-Marc and his wines, that drove me to sign up to attend his play, and subsequent lunch, which, both held at Daniel, comprised the official Thursday events of the 2015 La Paulée de New York.

The play (the subject of this post) was titled Meursault Les Luchets 2011 and would precede the Roulot-Roumier lunch (For those unfamiliar with the Domaine, Les Luchets is one of its terroirs and wines.). I had not fully recovered from the previous evening's Collectors Dinner with Armand Rousseau because of (i) over-consumption and (ii) I had left my new camera, with my pictures of the night's events, in the back seat of a taxi. And, frantic calls notwithstanding, I had been unable to recover same.

We traveled by taxi from our hotel to Daniel. As I entered the cab, I asked the driver if he had seen my camera. He looked at me as though I had recently been released from a psycho ward. "What camera you talkin' 'bout Bro," he said. "Nothing," I said, my resolve crumbling away as I silently called down the wrath of the heavens on all taxi drivers. Well, enough about my negligence. Let's get back to the matter at hand.

We had gotten to the restaurant pretty close to noon so by the time we had deposited our coats at the coat check (darn NYC winters), checked in, gotten our programs, and were shown to the room, all of the choice seats had been taken. All of the tables in the Daniel backroom had been taken out and chairs had been arranged in an arc around a raised platform set against the rear wall. That rear wall had two openings to a passage that led to who knows where. Towards the front of the stage there was a single wooden table and chair; bare if my recollection serves me well (I had pictures on my iPhone but I lost those when my phone fell into the urinal on Saturday night.). There was an additional chair on the platform stage right and a couch stage left. Stage right, and floor level, was another solitary chair with an accordion on the floor beside it.

We made our way to some open seats house left which gave us a less-than-head-on view of the stage. Shortly after we took our seats, a solitary figure wandered through the opening in the rear wall, sauntered over to the chair associated with the accordion, and began strapping into the instrument. All the while with a bemused smile on his face. According to the program, this was Eric Proud. And he sure acted that way.

Shortly after, another individual made his way onto the stage and sat on the chair stage right. As I was familiar with Jean-Marc, this could only be Gérard Chaillou, who was playing Largeau opposite Jean-Marc's Monplaisir. Finally, Jean-Marc strode onto the stage, an impassive look on his face, staring into the distance. He was carrying a valise which he placed on the table and from which, after rummaging around inside for awhile, he produced a bottle of wine and a corkscrew. While he was opening the wine, Largeau went off stage and returned with two wine glasses into which Jean-Marc poured generous portions. The wines were sniffed and then tasted. And then the dialogue began, each man tapping "into his own language, their words to describe taste linked to their own personal memories and to the sensory world that each and every one of us build and define patiently, year after year" -- Jean-Marc Roulot.

The passion and enthusiasm of the dialogue was captivating, a testament to the skill of the actors as the entire discourse was in French. There was a TV screen high up on the rear wall stage right which displayed subtitled translations of the dialogue but it was tiring -- and tiresome -- to keep switching between the text and the players. A lot was lost in this fashion. Secondly, some of the nuances and subtleties of the situations could not be captured adequately by the subtitled presentation as evidenced by knowing snickers and laughter and expressions of appreciation along the way by French-speaking members of the audience while I sat blank-faced and unknowing.

Sometime during the course of the proceedings Jean-Marc said words akin to "presenting Les Luchets 2011" and, magically, the Somms who were assisting in the event appeared in the glass-walled hallway house right bearing lighted trays with glasses of wine. They stood there momentarily before making their way into the audience and distributing the glasses to the attendees. It was Meursault Luchets 2011. And it was then that I realized what I had been missing all along. I had not had a drink all day.

After all the wine had been distributed, the actors returned to their labors. Including, at one point, a lusty soundtrack in which all three participated.

At the conclusion of the play the attendees showed their appreciation for the actors' efforts with multiple rounds of ovations. It was very revealing to see Jean-Marc in this new environment. I have tasted wine with him at his Domaine and seen him expounding on his wines and engaging in technical discussions with Raj Parr and another US winemaker who had joined us at the tasting. We had enjoyed joyous banter and a bottle of his wine at a chance encounter at Charle Bird's when we went up to NYC for the inaugural La Fete du Champagne. And here he had peeled away those personas, or covered them over with this, the persona of the accomplished, confident, the-world-is-my-oyster actor. I was mesmerized.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Friday, March 20, 2015

Before the Judgment of Paris, there was the Battle of Versailles: Different industry, same result

Before the Judgment of Paris, three words -- and an event -- of moment in the wine world, there was the Battle of Versailles, another event which pitted an upstart American industry against a dominant -- and domineering -- French counterpart. And once again the results were tectonic; and provided the protagonists with the fuel that drove them to previously unimaginable heights.

The industry of record in the Judgment of Paris was Wine; the industry of record in the Battle of Versailles was Fashion. The story of the Judgment of Paris is told in a book of the same name written by the only reporter present, George M. Taber. The story of the Battle of Versailles is recounted in a tome of the same name by Robin Givhan, Fashion Critic of the Washington Post and 2006 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fashion Criticism. Information about the Battle of Versailles used in this post is gleaned from an interview of the author by Renee Montagne on the March 19th edition of NPRs Morning Edition.

Prior to 1973, as was the case for the US wine industry prior to 1976, "Paris was everything" in the fashion industry and the American industry took its marching orders from the Parisian designers. "Whatever the French designers said was fashion, ... the Americans said, OK, that's fashion ..."

The Judgment of Paris (the event) took place at the Paris InterContinental Hotel on May 24, 1976 and pitted six Napa Chardonnays (vintage 1972 - 1974) and six Napa Cabernet Sauvignons (1969 - 1973) against four White Burgundies (1972 and 1973) and four Red Bordeauxs (1970 and 1971). The wines were tasted blind. Attendees, based on Taber's account, were the judges, Steven Spurrier (the event organizer), two unofficial observers, Taber, and the wait staff. Spurrier had secured the room at the hotel as a favor granted by the Food and Beverage Manager with the proviso that they had to be out before 6:00 pm as the room was committed to a wedding at that time. At the conclusion of the tasting, a California wine had been judged to be the best in each of the two categories.

The Battle of Versailles was held on November 28, 1973 at the Palace of Versailles and was at once a fundraiser to help in the restoration of the palace and a competition pitting five French couture designers against five up-and-coming American designers:

The disparity in time and setting notwithstanding, the show was a huge success for the Americans. According to Givhan, "It was a predominantly French crowd and they went bonkers ..." for the Americans. One of the keys to the American success was their models, 10 of whom were black. Again, the author: "There was a context of black chic that made the models particularly attractive. It was cool. It was progressive to use black models."

According to Robert Parker (a 2001 comment reproduced in Taber's book), "The Paris Tasting destroyed the myth of French supremacy and marked the democratization of the wine world. It was a watershed in the history of wine." According to Givhan, things also changed significantly after the Battle of Versailles, especially the way that American designers saw themselves. "... their success at Versailles convinced them that no, what they were producing wasn't less than, it was different, but it was just as good and in many ways more relevant to the way that women lived their lives."

It must have been traumatic to have lived in Paris in the mid-1970s. The persons responsible for the maintenance of French superiority took blows in that timeframe that they never fully recoverd from. And I am still waiting for Napa to build that richly deserved statue of Steve Spurrier right in the heart of its revitalized downtown.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

The industry of record in the Judgment of Paris was Wine; the industry of record in the Battle of Versailles was Fashion. The story of the Judgment of Paris is told in a book of the same name written by the only reporter present, George M. Taber. The story of the Battle of Versailles is recounted in a tome of the same name by Robin Givhan, Fashion Critic of the Washington Post and 2006 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fashion Criticism. Information about the Battle of Versailles used in this post is gleaned from an interview of the author by Renee Montagne on the March 19th edition of NPRs Morning Edition.

Prior to 1973, as was the case for the US wine industry prior to 1976, "Paris was everything" in the fashion industry and the American industry took its marching orders from the Parisian designers. "Whatever the French designers said was fashion, ... the Americans said, OK, that's fashion ..."

The Judgment of Paris (the event) took place at the Paris InterContinental Hotel on May 24, 1976 and pitted six Napa Chardonnays (vintage 1972 - 1974) and six Napa Cabernet Sauvignons (1969 - 1973) against four White Burgundies (1972 and 1973) and four Red Bordeauxs (1970 and 1971). The wines were tasted blind. Attendees, based on Taber's account, were the judges, Steven Spurrier (the event organizer), two unofficial observers, Taber, and the wait staff. Spurrier had secured the room at the hotel as a favor granted by the Food and Beverage Manager with the proviso that they had to be out before 6:00 pm as the room was committed to a wedding at that time. At the conclusion of the tasting, a California wine had been judged to be the best in each of the two categories.

The Battle of Versailles was held on November 28, 1973 at the Palace of Versailles and was at once a fundraiser to help in the restoration of the palace and a competition pitting five French couture designers against five up-and-coming American designers:

- French designers

- Yves St. Laurent

- Hubert de Givenchy

- Pierre Cardin

- Emmanuel Ungaro

- Marc Bohan (of Christian Dior)

- American designers

- Halston

- Oscar de la Renta

- Bill Blass

- Anne Klein

- Stephen Burrows

... there are men in, like, full livery with the white wigs and the uniforms. And people are arriving and they are the jet set of the time. And the theater where this took place is gilded and filled with blue velvet seats and fleur-de-lis, you know, embroidered on the curtains and the chandeliers.The French presentation at the Battle of Versailles lasted two hours while the American portion lasted 30 minutes. The French had constantly changing backdrops and a full orchestra to flesh out their effort while the American set was a sketch of the Eiffel Tower and its music was a taped Al Green and Barry White soundtrack.

The disparity in time and setting notwithstanding, the show was a huge success for the Americans. According to Givhan, "It was a predominantly French crowd and they went bonkers ..." for the Americans. One of the keys to the American success was their models, 10 of whom were black. Again, the author: "There was a context of black chic that made the models particularly attractive. It was cool. It was progressive to use black models."

According to Robert Parker (a 2001 comment reproduced in Taber's book), "The Paris Tasting destroyed the myth of French supremacy and marked the democratization of the wine world. It was a watershed in the history of wine." According to Givhan, things also changed significantly after the Battle of Versailles, especially the way that American designers saw themselves. "... their success at Versailles convinced them that no, what they were producing wasn't less than, it was different, but it was just as good and in many ways more relevant to the way that women lived their lives."

It must have been traumatic to have lived in Paris in the mid-1970s. The persons responsible for the maintenance of French superiority took blows in that timeframe that they never fully recoverd from. And I am still waiting for Napa to build that richly deserved statue of Steve Spurrier right in the heart of its revitalized downtown.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Thursday, March 19, 2015

Bentonite fining and protein stability

The need for bentonite fining is driven by the propensity of unstable proteins present in the wine to precipitate out in warm conditions and present as a cloudy haze in the bottle. By adding bentonite to the wine, significant amounts of these unstable proteins can be removed, minimizing the potential for haze. There is a down side to bentonite use though as over-fining can lead to flavor stripping. How do we minimize this? By determining the smallest amount of bentonite that can be used to remove the largest amount of protein with the least sensorial impact.

Protein and Polysaccharide Stability

Clarity has no apparent gustatory impact on wine quality but features prominently in the wine tasting schemes of both the Wine and Spirits Education Trust and the Guild of Sommeliers. The biggest challenges to wine clarity are proteins and polysaccharides, both of which, when unstable, manifest as hazes in the wine: off-white flakes in the case of the former and gelatinous masses in the case of the latter (Table 1, Harbertson).Wine proteins are derived from grape and yeast sources with their levels dependent on variety, vintage, maturity, fruit condition, pH, and processing methodology (Zoecklein 1988; Butzke). The protein’s ability to retain its stability is determined by its "isoelectric point" plus a number of other factors. Proteins can be either positively or negatively charged based on pH and their isoelectric points are attained when the positive and negative charges of the fractions are equal. They are least soluble (stable) at this point. In addition, the lower the difference between the pH and the isoelectric point, the lower the charge and, hence, the lower the solubility of the protein (Zoecklein 1988). Other factors impinging on solubility include temperature and the “concentration of wine complexing factors” and any one of these factors can cause protein precipitation. It should be noted that yeast proteins are not implicated in haze formation.

The overarching factor in haze formation, however, is heat which causes a denaturation and precipitation of the proteins or formation of insoluble complexes with polysaccharides or polyphenols.

As is the case with proteins, polysaccharides have both grape and yeast components. The grape elements come from healthy and Botrytis-infected fruit and are released by yeasts, lees, and bacteria (AWRI). Most polysaccharides are insoluble in ethanol and, as a result, the population is low in wine. Those that do remain can form a gelatinous mass in the presence of alcohol. As is the case with proteins, yeast-derived polysaccharides do not contribute to haze formation.

The hazes formed by proteins and polysaccharides are irreversible and must be removed. According to Budzke, “most consumers prefer a wine free from unappetizing-looking protein instabilities.”

Bentonite Fining

The approach utilized most frequently within the wine industry to remove unwanted juice/wine components is the use of fining agents. Fining agents are adsorptive or reactive materials which bind to undesirable elements with the denser compounds thus formed precipitating out, leaving the wine much clearer (as well as increasing its filterability). The effectiveness of a fining agent is dependent on (Zoecklein): the agent utilized, the method of preparation and addition, the quantity employed, wine pH, wine metal content, temperature, age of the wine, and previous treatments.

The fining agent that is most widely used to remove protein haze is bentonite, a clay with a layered structure which is added to wine as a clay-water suspension. Bentonite, having a slight negative charge, will bind with positively charged particles (such as proteins) and the complex thus formed will fall to the bottom. Bentonite fining will remove protein fractions with the largest cationic charge and will, especially if conducted simultaneously with bitartrate stabilization efforts, aid in the compaction of lees. The issues associated with bentonite fining are as follows (Butzke; Vincenzi, et al.):

- Flavor stripping

- Potential for oxidative damage if slurry mixing allows air exposure

- Fining before fermentation may lead to a sluggish fermentation due to stripping of certain growth factors

- Creates a solid waste problem

- Long settling times

- Certain quantity of wine lost as bentonite lees.

The process generally employed for bentonite fining is to conduct a fining trial wherein some number of samples are treated with regularly increasing doses of bentonite and with one of the samples untreated and held out as a control. The post-fining turbidity of each of these samples is then tested after which they are heated, cooled, and then turbidity-tested again. If the initial fining was sufficient, then the change in turbidity between tests would be less than 2 NTU (Nephelometruc Turbidity Units). If the change is greater than 2 NTU, additional fining trials would be run until the NTU fell below 2 because this shows that enough protein is left in the wine that it would precipitate under the right temperature conditions.

Assuming that all of the samples pass the turbidity test, the team is then able to conduct sensory evaluations to determine which sample attains protein stabilization with the least sensorial impact and then to use the trial results as the basis for bentonite fining of the production lots.

References

AWRI, Amorphous deposits, www.awri.com.au.

Butzke, Chris, Fining with Bentonite, Purdue Extension FS-53-W, www.extension.purdue.edu.

Harbertson, James F. A Guide to the Fining of Wines, Washington State University Extension Manual EMO16.

Vincenzi, Simone, et al., Removal of Specific Protein Components by Chitin Enhances Protein Stability in a White Wine, AJEV 56(3), 2005.

Zoecklein, Bruce (1988), Protein Stability Determination in Juice and Wine, Virginia Cooperative Extension, Publication 463-015.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Wednesday, March 18, 2015

Acidity vs sourness, bitterness vs astringency, and the tongue taste map: Some sensory misapprehensions

The overall taste of a wine is a combination of its odor, taste, and tactile perceptions as generated by specialized nerve cells resident in the nasal and oral cavities. Understanding the stimuli to which each of these specialized cells react is important to effective wine tasting and description. This brief post attempts to shed some light on a few oral sensory misapprehensions

Acidity versus Sourness

Acids play an important role in the cellular and metabolic functions of the grape berry and in the color and texture of the fermented wine. The primary acids found in grapes and fermented wine are tartaric, malic, and citric acids, as well as the tartaric and malic derivatives potassium hydrogen tartrate (cream of tartar) and potassium hydrogen malate. Acidity (as it relates to wine) is the measure of its acid content.

Total acidity is the sum of the hydrogen ions of both fixed and volatile acids that are present in the wine and, as such, is the most accurate representation of acid concentration. Total acidity is difficult to measure accurately, however, and so the more easily measurable titratable acidity (TA) is used as its proxy. Red table wines generally range between 0.6% and 0.8% TA as levels below 0.4% render the wine susceptible to infection and spoilage.

A second method for measuring the acidity of a wine is through observation of its pH (potential of hydrogen) level. The higher the number of hydrogen ions (H+) in a liquid, the more acidic it is while the higher the number of hydroxide ions (formed when an oxygen ion bonds to a hydrogen ion and represented as OH-) in the liquid, the higher its alkalinity. The pH scale runs from 0-14 with acidic solutions falling below 7.

Bitterness versus astringency

As indicated above, bitter is one of the five taste sensations. Sources of the bitter sensations in wine are flavonoid phenolics (primary), with several glycosoids, terpenes, and alkaloids contributing from time to time (Jackson, Wine Tasting). Bitterness and astringency are sometimes confused with each other because (i) they are both induced by the same compound; (ii) they are late-arriving (sweet and sour are the first taste sensations to make their presence felt); and (iii) they are slow to depart. The perception of bitterness is reduced by sugar, enhanced by alcohol, and hidden by astringency.

The Tongue Taste Map

The tongue taste map is truly a myth. A turn-of-the-century research paper indicated that certain areas of the tongue had been shown to be sensitive to specific tastes. Subsequent research had found these findings to be inaccurate because, in fact, most taste buds have receptors that can sense and report on all of the taste sensations. And though two-thirds of the taste buds are located on the tongue, they are also present in the soft palate and epiglottis and a few may even be located on the pharynx, larynx, and upper portion of the esophagus (Ronald S. Jackson, Wine Tasting: A Professional Handbook, Elsevier, 2002). Thenibble.com identified that early researcher as D.P Hanig, a German scientist, and also revealed that the findings were based on “subjective responses of volunteers.” This initial qualitative research was “coated” with numbers in 1942 by Edwards Boring of Harvard University (thenibble.com). Work in 1974 by Dr. Virginia Collins, and additional subsequent research, has shown that all tastes can be detected wherever there are taste buds yet the tongue taste map retains its Dracula persona.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Acidity versus Sourness

Acids play an important role in the cellular and metabolic functions of the grape berry and in the color and texture of the fermented wine. The primary acids found in grapes and fermented wine are tartaric, malic, and citric acids, as well as the tartaric and malic derivatives potassium hydrogen tartrate (cream of tartar) and potassium hydrogen malate. Acidity (as it relates to wine) is the measure of its acid content.

Total acidity is the sum of the hydrogen ions of both fixed and volatile acids that are present in the wine and, as such, is the most accurate representation of acid concentration. Total acidity is difficult to measure accurately, however, and so the more easily measurable titratable acidity (TA) is used as its proxy. Red table wines generally range between 0.6% and 0.8% TA as levels below 0.4% render the wine susceptible to infection and spoilage.

A second method for measuring the acidity of a wine is through observation of its pH (potential of hydrogen) level. The higher the number of hydrogen ions (H+) in a liquid, the more acidic it is while the higher the number of hydroxide ions (formed when an oxygen ion bonds to a hydrogen ion and represented as OH-) in the liquid, the higher its alkalinity. The pH scale runs from 0-14 with acidic solutions falling below 7.

Sour is one of the five recognized taste sensations (the others being sweet, bitter, salt, and umami) and is the human mechanism for recognizing the presence of acidity. According to Jackson (Wine Tasting, p.204), “sourness is a complex function of the acid, its dissociation constant and wine pH.”

To summarize then, acidity (as it relates to wine) is a measure of acid concentration in the wine while sourness is the way that that acidity manifests itself as a human taste sensation.

To summarize then, acidity (as it relates to wine) is a measure of acid concentration in the wine while sourness is the way that that acidity manifests itself as a human taste sensation.

Bitterness versus astringency

As indicated above, bitter is one of the five taste sensations. Sources of the bitter sensations in wine are flavonoid phenolics (primary), with several glycosoids, terpenes, and alkaloids contributing from time to time (Jackson, Wine Tasting). Bitterness and astringency are sometimes confused with each other because (i) they are both induced by the same compound; (ii) they are late-arriving (sweet and sour are the first taste sensations to make their presence felt); and (iii) they are slow to depart. The perception of bitterness is reduced by sugar, enhanced by alcohol, and hidden by astringency.

According to sensorysociety.org (and Richard Gawel, Secret of the Spit Bucket Revealed, aromadictionary.com), astringency is a tactile sensation, rather than a taste, and is primarily caused by polyphenolic compounds contained in certain foods (including wine) but can also be caused by acids, metal salts (such as alum), and alcohols. A key characteristic of astringency is the fact that it is difficult to clear from the mouth and, as such, builds in intensity on repeated exposure to the source. The source of astringency in wines is tannins, "a heterogeneous group of phenolic compounds" with properties to include: astringency (caused when the tannin binds with protein in saliva; evidenced by mouth pucker and a bitter aftertaste); bitterness; the ability to react with ferric chloride; and the ability to bind with proteins (Dr. Bruce Zoecklin, Enology Note #16).

There are two theories as to how astringency presents in the mouth (sensorysociety.org): (i) Polyphenols bind with the proteins in saliva and the resultant proline-rich proteins precipitate out (Gawel sees these precipitates as being reflected in the "stringy" salivary material that we spit into the buckets at wine tastings), thus reducing the ability of saliva to lubricate the mouth (this loss of "lubricity" is perceived as an increase in oral friction). (ii) The astringents directly effect the oral epithelium with a sensation of harshness presenting when the gums brush against the insides of the mouth.

There are two theories as to how astringency presents in the mouth (sensorysociety.org): (i) Polyphenols bind with the proteins in saliva and the resultant proline-rich proteins precipitate out (Gawel sees these precipitates as being reflected in the "stringy" salivary material that we spit into the buckets at wine tastings), thus reducing the ability of saliva to lubricate the mouth (this loss of "lubricity" is perceived as an increase in oral friction). (ii) The astringents directly effect the oral epithelium with a sensation of harshness presenting when the gums brush against the insides of the mouth.

According to both Gawel and sensorysociety.org, individuals with high saliva secretion rates will experience lower levels of astringency. Gawel alludes to three types of astringency:

- The feeling of having fine particles on the surface of the mouth; referred to by terms such as Powdery, Chalky, and Grainy

- Roughness of feeling inside the mouth; referred to by words such as Silky, Emery, Velvety, and Furry

- Causing the mouth to move; referred to by words such as Pucker, Chewy, Grippy, and Adhesive.

In summary, then, while sharing a few characteristics, bitterness and astringency differ in that the former is a taste sensation while the latter is a tactile sensation.

The Tongue Taste Map

The tongue taste map is truly a myth. A turn-of-the-century research paper indicated that certain areas of the tongue had been shown to be sensitive to specific tastes. Subsequent research had found these findings to be inaccurate because, in fact, most taste buds have receptors that can sense and report on all of the taste sensations. And though two-thirds of the taste buds are located on the tongue, they are also present in the soft palate and epiglottis and a few may even be located on the pharynx, larynx, and upper portion of the esophagus (Ronald S. Jackson, Wine Tasting: A Professional Handbook, Elsevier, 2002). Thenibble.com identified that early researcher as D.P Hanig, a German scientist, and also revealed that the findings were based on “subjective responses of volunteers.” This initial qualitative research was “coated” with numbers in 1942 by Edwards Boring of Harvard University (thenibble.com). Work in 1974 by Dr. Virginia Collins, and additional subsequent research, has shown that all tastes can be detected wherever there are taste buds yet the tongue taste map retains its Dracula persona.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

Monday, March 16, 2015

American Gymkhana: Modern Indian cuisine wends its way to Orlando

Raj Parr recently visited Orlando for a tasting of his domestic and Burgundy wines. At the completion of the tasting, he tarried a bit to taste some of the wines that Ron and I had brought to the event. In discussing his schedule for the remainder of the day, he mentioned that he was having dinner at American Gymkhana. I knew that it was a new restaurant on the Orlando scene and that the cuisine was Indian but we had not eaten there (and not because of lack of effort on my wife's part). When I ran into Raj at La Paulée I asked him about his experience at American Gymkhana and he said the food had been surprisingly good. In the intervening period, my wife had gotten excellent reviews from friends who had visited. With this growing mountain of evidence that this restaurant was cooking good food, my wife would be restrained no longer. We were going to American Gymkhana. And so we did. Last Thursday.

American Gymkhana is owned by Restaurateur Rajesh Bhardwaj, the Founder and CEO of Junoon New York (the only Michelin-starred Indian-cuisine restaurant in NYC) and Junoon Dubai. I struggled a bit with the choice of the name, both before and after its meaning was explained. Gymkhana's were the meeting places of the elite during the period of the British Raj in India. Go figure.

The restaurant is located on the top floor of the westernmost building in the "Vines Plaza" in the heart of Sand Lake Road's Restaurant Row. You climb two sets of stairs to get to the reception area and arrive there winded. Our guests had not yet arrived so we repaired to the bar. The bar, and associated lounge, were both pleasing to the eye; places where you would want to sit and have a drink or two. My wife is currently into a Jalapeno Grey Goose cocktail that the mixologist was unfamiliar with but which he constructed magnificently once told the components.

Once our guests arrived, we were shown to our seats. The restaurant is spacious; and the distribution of the seating adds to the sense of expansiveness. A large, clean-looking, open kitchen is sited at the eastern end of the restaurant. The barrel ceilings provide a sense of coziness and are accented by purple-hued lighting.

The menu was clean and simple with between six and eight items in each category and each dish having a subtext describing its components.

The first item brought to our table was a basket of Naan Bread. This leavened, oven-baked flatbread was the canary; except that there was no coalmine. It was heralding the gustatory pleasures to come. It was freshly made and accompanied by a mint dipping sauce. It had great flavor and texture and really did not need any hand-holding.

The Amouse Bouche was a Pineapple Salsa on a Masala Cracker. Cilantro, spiciness, and light tanginess. The mix of textures was intriguing with the crackling crunch of the cracker contrasting with the give of the pineapple chunks.

We had each ordered a dish from the starters and they began to arrive. The Gymkhana Chicken looked a little much but was a treat on the palate. A dash of Yogurt Sauce and a portion of seasonal Lettuce were in attendance in the event that cooling influences were necessary but the intense flavors, the spiciness, and the temperature were right up my alley.

I also ordered a dish called Adraki Gobhi which was a cauliflower fritter made with ginger and galangal (also a part of the ginger family). At first glance it looked like a meatball but tasted anything but. The spicy red sauce was the cocoon for cauliflowers that had been firmed-up by slight roasting.

The Aloo Chaat was a "potato slider" with Yukon Potatos on the top, Purple Potatos on the bottom (in the styling of a potato chip), and Fingerlings in the middle. These were accompanied by a seasonal Fruit Chutney.

We accompanied the starters with a bottle of Paul Déthune Champagne.

My wife ordered a Lobster dish for her main course while I ordered Lamb Chops. Our table companions ordered Lamb Curry, Goat Curry, and Fish so that we could sample a broad array of the fare on offer. The Lobster dish was comprised of two whole Maine lobsters that were Saffron-Marinated and accompanied by a spiced lobster butter. The Nahile Lamb Chops were cooked with whiskey, ginger, black cardamom, and a garlic-whipped yogurt. The lobster was excellent but I could not wrap my head (or palate) around the Lamb. It had a cloying texture and the meat was not firm enough for my liking. I had gone from some very spicy foods to a milky, taste-free dish. I did not like it (In conversations the following day, the Chef told my wife that this meal was designed for people who did not like spicy meals. I wish the waiter had told me that.).

One of my tablemates had gotten the Goat Roganjosh, which is goat on the bone braised in Kashmiri chili and clarified butter, while the other had gotten the Lamb Vindaloo which was constructed with apple cider vinegar, Goan chilies, black pepper, and twice-fried potatos. Both of these were outstanding dishes, especially when some Roti was added to the mix. I lived in my neighbors plates.

At the conclusion of the dinner my wife asked the waiter about the owner and the waiter said that he happened to be in the building that evening. We asked to speak to him and once he had concluded the meeting with which he was engaged, he came over. Nice conversation. We thanked him for bringing this venture to Orlando. He talked a bit about the concept and about the fact that he was flying out from Orlando to Dubai to visit the Junoon there. We also met the Chef (Aarthi Sampath), and congratulated her on the food, and the Wine Director (David Pennisi) with whom we tasted a few wines.

All in all a wonderful evening. This modern twist on Indian cooking is pleasing on the palate and wallet.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

American Gymkhana is owned by Restaurateur Rajesh Bhardwaj, the Founder and CEO of Junoon New York (the only Michelin-starred Indian-cuisine restaurant in NYC) and Junoon Dubai. I struggled a bit with the choice of the name, both before and after its meaning was explained. Gymkhana's were the meeting places of the elite during the period of the British Raj in India. Go figure.

The restaurant is located on the top floor of the westernmost building in the "Vines Plaza" in the heart of Sand Lake Road's Restaurant Row. You climb two sets of stairs to get to the reception area and arrive there winded. Our guests had not yet arrived so we repaired to the bar. The bar, and associated lounge, were both pleasing to the eye; places where you would want to sit and have a drink or two. My wife is currently into a Jalapeno Grey Goose cocktail that the mixologist was unfamiliar with but which he constructed magnificently once told the components.

Once our guests arrived, we were shown to our seats. The restaurant is spacious; and the distribution of the seating adds to the sense of expansiveness. A large, clean-looking, open kitchen is sited at the eastern end of the restaurant. The barrel ceilings provide a sense of coziness and are accented by purple-hued lighting.

The menu was clean and simple with between six and eight items in each category and each dish having a subtext describing its components.

The first item brought to our table was a basket of Naan Bread. This leavened, oven-baked flatbread was the canary; except that there was no coalmine. It was heralding the gustatory pleasures to come. It was freshly made and accompanied by a mint dipping sauce. It had great flavor and texture and really did not need any hand-holding.

The Amouse Bouche was a Pineapple Salsa on a Masala Cracker. Cilantro, spiciness, and light tanginess. The mix of textures was intriguing with the crackling crunch of the cracker contrasting with the give of the pineapple chunks.

We had each ordered a dish from the starters and they began to arrive. The Gymkhana Chicken looked a little much but was a treat on the palate. A dash of Yogurt Sauce and a portion of seasonal Lettuce were in attendance in the event that cooling influences were necessary but the intense flavors, the spiciness, and the temperature were right up my alley.

I also ordered a dish called Adraki Gobhi which was a cauliflower fritter made with ginger and galangal (also a part of the ginger family). At first glance it looked like a meatball but tasted anything but. The spicy red sauce was the cocoon for cauliflowers that had been firmed-up by slight roasting.

The Aloo Chaat was a "potato slider" with Yukon Potatos on the top, Purple Potatos on the bottom (in the styling of a potato chip), and Fingerlings in the middle. These were accompanied by a seasonal Fruit Chutney.

We accompanied the starters with a bottle of Paul Déthune Champagne.

My wife ordered a Lobster dish for her main course while I ordered Lamb Chops. Our table companions ordered Lamb Curry, Goat Curry, and Fish so that we could sample a broad array of the fare on offer. The Lobster dish was comprised of two whole Maine lobsters that were Saffron-Marinated and accompanied by a spiced lobster butter. The Nahile Lamb Chops were cooked with whiskey, ginger, black cardamom, and a garlic-whipped yogurt. The lobster was excellent but I could not wrap my head (or palate) around the Lamb. It had a cloying texture and the meat was not firm enough for my liking. I had gone from some very spicy foods to a milky, taste-free dish. I did not like it (In conversations the following day, the Chef told my wife that this meal was designed for people who did not like spicy meals. I wish the waiter had told me that.).

One of my tablemates had gotten the Goat Roganjosh, which is goat on the bone braised in Kashmiri chili and clarified butter, while the other had gotten the Lamb Vindaloo which was constructed with apple cider vinegar, Goan chilies, black pepper, and twice-fried potatos. Both of these were outstanding dishes, especially when some Roti was added to the mix. I lived in my neighbors plates.

At the conclusion of the dinner my wife asked the waiter about the owner and the waiter said that he happened to be in the building that evening. We asked to speak to him and once he had concluded the meeting with which he was engaged, he came over. Nice conversation. We thanked him for bringing this venture to Orlando. He talked a bit about the concept and about the fact that he was flying out from Orlando to Dubai to visit the Junoon there. We also met the Chef (Aarthi Sampath), and congratulated her on the food, and the Wine Director (David Pennisi) with whom we tasted a few wines.

|

| Aarthi Sampath, Chef de Cuisine |

|

| David Pennisi, Wine Director |

|

| What we drank |

All in all a wonderful evening. This modern twist on Indian cooking is pleasing on the palate and wallet.

©Wine -- Mise en abyme

.png)